Body-Worn Cameras and Dashboard Cameras: Final Recommendations

This report concludes Phase III of OPO’s three-phase process to facilitate a rewrite of Austin Police Department (APD) policies related to body-worn and dashboard cameras.

Contact Information

Office of Police Oversight |

Main office:512-974-9090

Complaint and thank-you hotline: 512-972-2676

|

Executive Summary

Executive Summary 1 of 8

OPO's Three-Phase Approach

This report concludes Phase III of OPO’s three-phase process to facilitate a rewrite of Austin Police Department (APD) policies related to body-worn and dashboard cameras. In accordance with resolutions passed by the Austin City Council in June 2020, the City Manager has directed OPO to facilitate a rewrite of the APD policy manual, known as the General Orders.[1] OPO worked with the City Manager’s Office to develop a three-phase approach to accomplish this task.

Background Information

In Phase I, OPO conducts a preliminary analysis of APD’s current policy language on specific topics. All analyses are made available on OPO’s website.

In Phase II, OPO works with community partners and stakeholders to gather input from the public about proposed changes to policies. This outreach effort includes events, surveys, and other forms of community engagement.

In Phase III, OPO submits policy recommendations and community feedback to the City Manager, City Council, and APD. Then, APD is responsible for working with the City Manager’s Office to review and act on these final recommendations.

Applying the Three-Phase Approach to APD’s Body-Worn and Dashboard Camera Policies

OPO used this same three-phase approach to address APD’s policies on body-worn and dashboard cameras.

In January 2022, OPO published its Phase I report examining whether APD’s body-worn and dashboard camera policies aligned with best practices, relevant laws, and the City of Austin’s policies, goals, and values. In the report, OPO identified several areas for improvement within APD’s current policies, including the need to:

- Consider the role of vendors and community input in the policymaking process;

- Revise the purpose statements for each policy to prioritize the use of body-worn and dashboard cameras to further citywide efforts to eliminate bias-based profiling and reduce the use of force;

- Revise the body-worn camera policy to align with state law, specifically House Bill 929 (The Botham Jean Act), and add definitions to address gaps in state law;

- Clearly define pertinent terms and requirements related to starting and stopping a recording;

- Require more documentation around recording, delayed recording, and failing to record;

- Revise certain policy titles to accurately reflect content;

- Require supervisor inspections of dashboard camera recordings; and

- Modify enforcement and discipline practices for violations of these policies.

In February 2022, OPO launched Phase II of the rewrite process with a community engagement campaign. Between February and April 2022, OPO gathered community feedback on APD’s body-worn and dashboard camera policies and OPO’s recommendations. The campaign resulted in four virtual events and 525 survey submissions.

In April 2022, OPO began Phase III of the rewrite process, compiling and analyzing the data collected in Phase II. During Phase III, OPO also OPO contacted police departments and/or civilian oversight offices in 15 cities across the country to learn more about their policy development processes. OPO concluded Phase III by incorporating community feedback and research findings into final policy recommendations.

Executive Summary 2 of 8

Outline of Phase III Report Content

This report discusses OPO’s Phase III research, data findings, and final policy recommendations on the topic of body-worn and dashboard cameras, and policy development more generally.

The report is organized into the following four sections:

A. Overarching Recommendations;

B. Policy Language Recommendations;

C. Data Analysis Discussion & Findings; and

D. The Role of Vendors & Community Input in Policy Development.

The pages that follow offer summaries of each of these sections.

Executive Summary 3 of 8

Summary of Overarching Recommendations

OPO offers 17 policy and process recommendations based on findings from community survey data and research into the policymaking processes of other U.S. police departments.

Below are condensed descriptions of these recommendations. Read the full descriptions here.

OPO recommends that APD:

- Request and use public feedback when writing and developing policies on the use of body-worn and dashboard cameras.

- Update the purpose and scope sections of the body-worn and dashboard camera policies to emphasize the City of Austin’s commitment to reducing racial profiling, reducing the use of force, and improving community relationships and make it clear that these cameras can play a role in supporting that effort.

- Provide clearer definitions and guidelines when laws are unclear.

- Provide officers with clearer instructions for when they must start and stop recording with their cameras. This should apply to the capture of video and audio.

- Require officers to acknowledge their use of body-worn cameras and dashboard cameras in police reports.

- Provide instructions for officers to use when telling community members that their interaction is being recorded.

- Require supervisors to make sure that dashboard cameras and body-worn cameras are in working condition and being used correctly.

- Require that potential violations of the body-worn camera and dashboard camera policies be investigated.

- Partner with OPO to develop a transparent and formalized process for soliciting and incorporating community feedback during policy development.

- Work with OPO to build an engagement process that considers different mediums and formats to balance large-scale, community-wide outreach with targeted outreach aimed at those who have lived experience and are most impacted by policing in Austin and the specific policies under review.

- Devote human and economic resources to collecting and synthesizing community feedback for policy drafting.

- Publish a schedule of planned updates to the General Orders at the beginning of each calendar year and update it as needed.

- Publish information about the source of its policies.

- Publish background information to explain the reason for each policy change.

- Publish and share policies in a manner that is accessible to those who have disabilities and communication barriers.

- Reconsider the role that vendors play in the policymaking process.

- Meet with OPO to discuss the recommendations stemming from this project and identify the processes and resources necessary to act on them.

Executive Summary 4 of 8

Summary of Policy Language Recommendations

OPO’s policy language recommendations include revisions to almost all provisions of APD’s current policies on body-worn and dashboard cameras. This report provides clean copies of OPO’s proposed revisions to the policy language, information about the source of the proposed language, APD’s current policies, and redlined versions of all proposed policy changes.

The following are condensed descriptions of some of the key issues addressed by these recommendations. Read the full descriptions here.

- Compliance with the amendments to Section 1701.655 of the Texas Occupations Code under Texas House Bill 929 (the Botham Jean Act)

- Compliance with Section 1701.657(c) of the Texas Occupations Code

- More definitions, including terms like “active participation,” “investigation,” and “law enforcement purposes,” which are used (but left undefined) under Texas law. OPO also defined other pertinent terms like “activate,” “deactivate,” and “docking.”

- Clearer requirements related to the following;

- Documentation of recordings;

- Notice of recording;

- Activation/deactivation of video recording;

- Activation/deactivation of audio recording;

- Equipment testing by employees; and

- Inspections by supervisors

5. Investigation requirements

Executive Summary 5 of 8

Summary of Data Analysis Discussion & Findings

This report discusses the insights and analyses of survey data collected from Austin community members through a citywide survey provided between February and April 2022. OPO received 525 survey submissions, including 443 digital submissions and 82 paper submissions.

OPO’s analysis included an analysis of respondents’ self-reported demographic information. The following are examples of some of the demographic data:

- Race/ethnicity:

- 51% of respondents identified as White.

- 11% of respondents identified as Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish.

- 7% of respondents identified as Black or African American.

2. Social class:

- 55% of respondents identified as middle class or upper-middle class.

- 7% of respondents identified as low-income or poor.

3. Physical and mental health conditions:

- 33% of respondents reported having a physical or mental health condition

- 73% of these respondents reported having one or more mental health conditions.

- 18% of these respondents reported having both a mental and physical health condition.

The following were key takeaways from the survey data:

- Most survey respondents were in favor of each OPO recommendation. For example:

- 66% of respondents believe the City should request and use public feedback when writing rules.

- 66% of respondents support revising APD policies to provide officers with clearer instructions for when they must stop recording audio and video with their cameras.

- 62% of respondents believe police officers should be required to acknowledge their use of body-worn cameras and dashboard cameras in a police report.

2. When compared to digital surveys, paper surveys captured more individuals who identified as low-income (27% versus 4%) and had a higher percentage of individuals who identified as Black or African American (23% versus 4%). In addition, the analysis revealed variations in participation from individuals identifying as male (54% versus 39%) or non-binary/genderqueer/genderfluid (9% versus 2%).

- These variations were among several identified when OPO compared digital and paper survey responses. Taken together, these variations suggest a need to potentially modify future outreach methods and reconsider the role of digital surveys in collecting community input.

Executive Summary 6 of 8

Summary of the Role of Vendors and Community Input in Policy Development

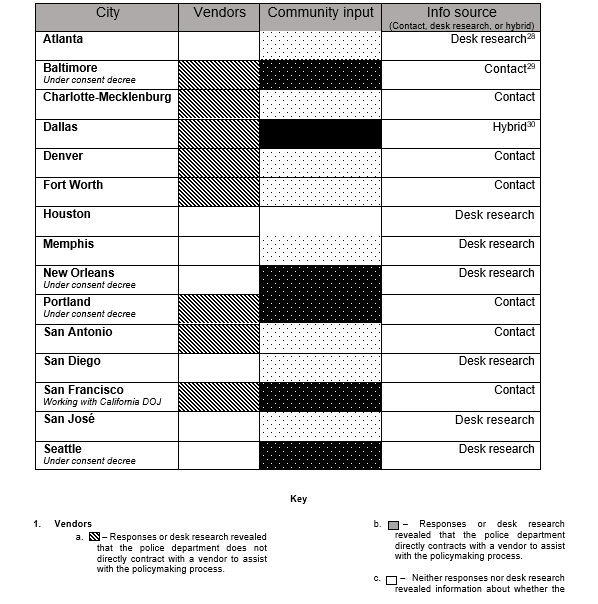

As part of Phase III, OPO contacted police departments and oversight offices in 15 cities across the country to learn more about the processes they use to draft police department policies.

The cities examined included the following:

- Atlanta

- Baltimore

- Charlotte

- Dallas

- Denver

- Fort Worth

- Houston

- Memphis

- New Orleans

- Portland

- San Antonio

- San Diego

- San Francisco

- San José

- Seattle

This report discusses important findings about how the police departments in these cities research and formulate their policies, whether they use vendor policies and the extent to which they use community input to inform their policies.

Below are key findings from this research:

1. None of these 8 responding cities use vendors for policy writing.

The responding cities included Baltimore, Charlotte, Dallas, Denver, Fort Worth, Portland, San Antonio, and San Francisco. OPO conducted desk research on the 7 other cities and did not find any information about whether they currently contract with vendors for policy writing.

2. Vendor policies may indirectly impact cities that keep their policymaking processes in-house.

This suggests a need for increased transparency around the source of policy language, ensuring that policymakers are as fully informed as possible about the role of vendors and other contributors and can share that information openly with community members.

3. Police departments use a range of methods to research best practices and collect community input, and the departments with more structured processes for community input take a multi-faceted approach that includes opportunities for both a broad response and a more focused response.

The San Francisco Police Department stood out as a police department with one of the most robust and transparent processes for incorporating community input into the policymaking process, utilizing structured focus groups, a public comment period, and structured mechanisms for collaborating with San Francisco’s civilian oversight office.

4. Many oversight entities redirected questions about policymaking to their city’s police department, often citing a lack of detailed information.

This may suggest that current policymaking processes in these police departments lack transparency or that oversight bodies in these cities are not directly and routinely involved in the departments’ policymaking processes.

Executive Summary 7 of 8

Conclusion

OPO looks forward to working with APD and City leadership to act on these recommendations and continue the important work of revising the General Orders to incorporate community input, increase transparency, and enhance accountability.

Executive Summary 8 of 8

Endnotes

Below are the endnotes for the Executive Summary section.

[1] See Resolution 20200611-050 (PDF, 146KB), Austin City Council (June 11, 2020), accessed August 15, 2022, Resolution 20200611-095 (PDF, 279 KB), Austin City Council (June 11, 2020), accessed August 15, 2022; Resolution 20200611-096 (PDF, 424 KB), Austin City Council (June 11, 2020), accessed August 15, 2022.

Overarching Recommendations

Overarching Recommendations 1 of 2

Recommendations for Improving APD’s Body-worn and Dashboard Camera Policies

The following recommendations propose actionable steps for improving APD’s body-worn and dashboard camera policies. These recommendations are informed by information gathered during Phases II and III of the rewrite process.

Based on findings from the community survey data, OPO recommends that APD implement OPO’s preliminary recommendations to the body-worn and dashboard camera policies through the following changes:

- Request and use public feedback when writing and developing policies on the use of body-worn and dashboard cameras.

- Update the purpose and scope sections of the body-worn and dashboard camera policies to emphasize the City of Austin’s commitment to reducing racial profiling, reducing the use of force, and improving community relationships and make it clear that these cameras can play a role in supporting that effort.

- Provide clearer definitions and guidelines when laws are unclear.

- Provide officers with clearer instructions for when they must start and stop recording with their cameras. This should apply to the capture of video and audio.

- Require officers to acknowledge their use of body-worn cameras and dashboard cameras in police reports.

- Provide instructions for officers to use when telling community members that their interaction is being recorded.

- Require supervisors to make sure that dashboard cameras and body-worn cameras are in working condition and being used correctly.

- Require that potential violations of the body-worn camera and dashboard camera policies be investigated.

These eight recommendations are directly tied to OPO’s preliminary recommendations.

Overarching Recommendations 2 of 2

Recommendations for Improving APD’s Policy Development Practices

The following recommendations propose actionable steps for improving APD’s policy development practices. These recommendations are informed by information gathered during Phases II and III of the rewrite process.

Many of these police departments work to embed accountability into their policymaking processes by collecting community input, but only a few departments appear to have regular, codified processes that gather community feedback before drafting begins and at more than one stage of the process.

Recent research developed by academic circles, nonprofits, think tanks, and governmental organizations points to the need for more tailored policymaking processes.[1] Human- or user-centered policymaking is a process that works with end-users to co-design policies.[2] It is a process that combines agile methodologies, human-centered design, and human-centered policymaking.[3] Agile methodologies are iterative, and work is re-evaluated as it is done to ensure that value is continuously created.[4] Human-centered design is a way of working that puts impacted individuals in the center, creating processes that meet people’s needs and experiences.[5] Human-centered policymaking increases accountability and buy-in by creating policies that are relevant to stakeholders.[6]

As it relates to APD’ body-worn and dashboard camera policies, OPO’s community survey data revealed that many community members may not be familiar with APD’s body-worn and dashboard camera programs and policies. Body-worn and dashboard cameras play a vital role in improving transparency related to policing. As a result, APD must work to ensure that community members understand what they are, how they work, and how they’re used by APD officers.

Therefore, OPO also recommends that APD show its dedication to transparency and accessible, community-centered policy development by:

9. Partnering with OPO to develop a transparent and formalized process for soliciting and incorporating community feedback during policy development.

- This process should standardize and clearly communicate timelines and processes.

- The process should also give community members an active role in the formulation and development of policies that impact them, ensuring that those individuals who are most impacted are involved in crafting policies from the very beginning and have designated roles at crucial stages of development.

- Decisions as to which policies should require community input should also be informed by feedback from the public.

10. Working with OPO to build an engagement process that considers different mediums and formats to balance large-scale, community-wide outreach with targeted outreach aimed at those who have lived experience and are most impacted by policing in Austin and the specific policies under review.

- This may call for combining methods like community-wide surveys, small focus groups, and one-on-one interviews.

11. Devoting human and economic resources to collecting and synthesizing community feedback for policy drafting (i.e., full-time APD staff that is dedicated to overseeing outreach and engagement for the purposes of policy revisions).

12. Publishing a schedule of planned updates to the General Orders at the beginning of each calendar year and updating it as needed.

- This should be accompanied by instructions that clearly communicate the ways in which community members can provide feedback.

- Methods for feedback should be accessible to a range of stakeholders and consider things like disability access, language access, and the digital divide.

13. Publishing information about the source of its policies.

- In practice, this would include information about the cities and/or organizations the language came from, whether any source language came from vendors (or entities that work with vendors), whether the policies were developed with community input, and which internal and external stakeholders worked on the language (e.g., other City departments, consultants, or organizations like the Police Executive Research Forum).

14. Publishing background information to explain the reason for each policy change.

- OPO recommends posting this information along with a redlined version of the policy language.

15. Publishing and sharing policies in a manner that is accessible to those who have disabilities and communication barriers.

- In practice, this would involve the use of various mediums to support those who, for example, read second languages or have low vision or blindness, limited literacy, or neurological conditions. Currently, APD publishes its policies, as well as changes to policy, on the APD website by posting links to PDF documents. These documents may not be accessible to those who use screen readers, and they are only posted in English.

16. Reconsidering the role that vendors play in the policymaking process.

- The use of vendors for policy drafting or template language can add an unnecessary level of obscurity to the policymaking process, and it does not appear to be a best practice utilized by peer departments.

17. Meeting with OPO to discuss the recommendations stemming from this project and identify the processes and resources necessary to act on them.

Policy Recommendations

Policy Recommendations 1 of 3

Introduction

The pages that follow lay out the details of OPO’s final policy language recommendations to improve APD’s body-worn camera policies (General Order 303) and dashboard camera policies (General Order 304), including:

- A summary of final policy language recommendations;

- Final policy language recommendations;

- Source information;

- APD’s current policy language; and

- Redlined versions of APD’s policies that track all changes proposed by OPO.

Policy Recommendations 2 of 3

Policy Recommendations

Below are some of the key policy issues addressed by OPO’s recommendations:

- Compliance with the amendments to Section 1701.655 of the Texas Occupations Code under Texas House Bill 929, which requires that:

- Body-worn camera policies include a provision related to “to the collection of a body worn camera, including the applicable video and audio recorded by the camera, as evidence.”[1]

- Addressed by OPO’s revision to Section 303.9 of the General Orders.

- Body-worn camera policies “require a peace officer equipped with a body-worn camera and actively participating in an investigation to keep the camera activated for the entirety of the officer’s active participation in the investigation unless the camera has been deactivated in compliance with [police department] policy.”[2]

- Addressed by OPO’s revision to Section 303.2 and Section 303.5.3(b) of the General Orders.

- Body-worn camera policies include a provision related to “to the collection of a body worn camera, including the applicable video and audio recorded by the camera, as evidence.”[1]

- Compliance with Section 1701.657(c) of the Texas Occupations Code, which requires that:

- an officer “who does not activate a body worn camera in response to a call for assistance must include in the officer’s incident report or otherwise note in the case file or record the reason for not activating the camera.”[3]

- Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.5.2(h) of the General Orders.

- an officer “who does not activate a body worn camera in response to a call for assistance must include in the officer’s incident report or otherwise note in the case file or record the reason for not activating the camera.”[3]

- More definitions, including terms like:

- “Active participation,” “investigation,” and “law enforcement purposes,” which are used (but left undefined) under Texas law. OPO also defined other pertinent terms like “activate,” “deactivate,” and “docking.”

- Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.2 of the General Orders.

- “Active participation,” “investigation,” and “law enforcement purposes,” which are used (but left undefined) under Texas law. OPO also defined other pertinent terms like “activate,” “deactivate,” and “docking.”

- Clearer requirements related to

- Documentation of recordings

- Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.5.2(g) and Section 304.4.1(e) of the General Orders.

- Notice of recording

- Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.6 and Section 304.5 of the General Orders.

- Activation/deactivation of video recording

- Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.5.3(b) and Section 304.4.2(a) of the General Orders.

- Activation/deactivation of audio recording

- Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.5.3(b)(7) and Section 304.4.2(b) of the General Orders.

- Equipment testing by employees

- “Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.5.2(d) and Section 304.4.1(b) of the General Orders.

- Inspections by supervisors

- Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.8 and Section 304.2 of the General Orders.

- Documentation of recordings

- Requiring investigations into potential violations of body-worn and dashboard camera policies

- Addressed by OPO’s revisions to Section 303.15 and Section 304.14 of the General Orders.

For more information

View (PDF, 643 KB) OPO's recommended language for APD's Body-worn camera policies (General Order 303), the current policy language, and a version showing OPO's recommended changes.

View (PDF, 533 KB)OPO's recommended language for APD's Body-worn camera policies (General Order 304), the current policy language, and a version showing OPO's recommended changes.

Policy Recommendations 3 of 3

Endnotes

Below are the endnotes for Policy Recommendations.

View (PDF, 3.3MB) the sources OPO used to create these policy recommendations.

[1] Botham Jean Act, H.B. 929, 87th Legislature, Regular Session, 2021.

[2] Botham Jean Act, H.B. 929, 87th Legislature, Regular Session, 2021.

[3] Texas Occupations Code §1701.657(c).

Data Analysis Discussion and Findings

Data Analysis Discussion and Findings 1 of 7

Introduction

In early 2022, OPO conducted a community engagement campaign to gather feedback on APD’s current policies and OPO’s recommendations related to body-worn and dashboard cameras.

The campaign, which included outreach through events and surveys, collected two types of data:

Quantitative data: Data is data that describes a quantity, amount, or range. An example of quantitative data would be age, age groups, or salary.

Qualitative data: Qualitative data or text data that cannot be formatted or classified into different groups. Unstructured data is generally analyzed through manual synthesis or using natural language processing tools.

In Phase III, OPO compiled and analyzed the data collected in Phase II.

The following pages discuss the insights and analyses of quantitative data collected from Austin community members through a citywide survey provided from February to April 2022. OPO received 525 survey submissions, including 443 digital submissions and 82 paper submissions.

Takeaways

- The majority of respondents supported OPO’s recommendations across the board.

OPO analyzed data from over 500 surveys submitted by community members. Interestingly, while the medium through which individuals responded impacted the level of support (with paper surveys being more supportive), OPO’s recommendations were supported across the board.

2. Paper surveys captured more individuals who identified as low-income and had a higher percentage of individuals who identified as Black or African American. In addition, the analysis revealed interesting variations in participation for respondents who identified as male or non-binary/genderqueer/genderfluid.

These variations were among several identified when OPO compared digital and paper survey responses. Taken together, these variations suggest a need to potentially modify future outreach methods and reconsider the role of digital surveys in collecting community input.

Data Analysis Discussion and Findings 2 of 7

Details of Key Insights

OPO analyzed survey data to:

- Determine whether respondents were in favor of OPO’s proposed changes to APD’s body-worn and dashboard camera policies;

- Identify overarching themes in responses; and

- Learn more about the communities OPO is reaching through surveys, including demographic information, past interactions with APD officers, and knowledge of APD policy.

The two key insights from OPO’s analysis of the survey data were as follows:

1) Most respondents were in favor of each OPO recommendation.

- 66% of respondents believe the City should request and use public feedback when writing rules.

- 61% of respondents want the body-worn and dashboard camera program to include more community input.

- 66% of respondents believe community involvement positively impacts government accountability.

- 61% of respondents support updating APD policies to emphasize the City of Austin’s commitment to reducing racial profiling and improving community relationships.

- 69% of respondents believe police department policies should provide clearer definitions and guidelines when laws are unclear.

- 66% of respondents support revising APD policies to provide officers with clearer instructions for when they must stop recording audio and video with their cameras.

- 62% of respondents believe police officers should be required to acknowledge their use of body-worn cameras and dashboard cameras in a police report.

- 58% of respondents believe APD should provide instructions for officers to use when telling community members that their interaction is being recorded.

- 67% of respondents believe APD policies should require supervisors to make sure dashboard cameras and body-worn cameras are in working condition and being used correctly.

- 61% of respondents believe potential violations of the body-worn camera and dashboard camera policies should require an investigation.

2) Paper surveys captured more individuals who identified as low-income and had a higher percentage of individuals who identified as Black or African American. In addition, the analysis revealed interesting variations in participation for respondents who identified as male or non-binary/genderqueer/genderfluid.

Below are a few examples of findings from this comparative analysis. Further data is available here.

- % Respondents identifying as low-income

- 27% of paper survey respondents

- 4% of digital survey respondents

- % Respondents identifying as male

- 54% of paper survey respondents

- 39% of digital survey respondents

- % Respondents identifying as non-binary / genderqueer / genderfluid

- 9% of paper survey respondents

- 2% of digital survey respondents

- % Respondents identifying as Black or African American

- 23% of paper survey respondents

- 4% of digital survey respondents

Data Analysis Discussion and Findings 3 of 7

Demographics

In addition to conducting an analysis of sentiment and a deeper analysis of survey trends, OPO analyzed respondents’ demographic data.

All survey respondents were able to self-identify as to the following:

- Race/ethnicity;

- Language(s) spoken at home;

- Gender identity;

- LGBTQIA+ identity;

- Age;

- Social class;

- Physical and mental health conditions;

- Residential ZIP code; and

- Employment ZIP code.

Demographic categories and terms were constructed after researching survey best practices [1] and consulting with the City Demographer [2]. Below are the results of this analysis:

Race/ethnicity:

- 51% of respondents identified as White.

- 11% of respondents identified as Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish.

- 7% of respondents identified as Black or African American.

Language(s) spoken at home:

- 71% of respondents said they speak English at home.

- 16% of respondents said they speak two or more languages at home.

- 1% of respondents said they speak only Spanish at home.

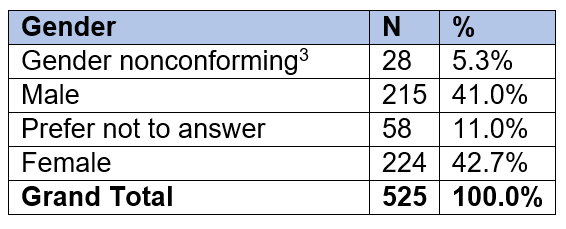

Gender identity:

- 43% of the respondents self-identified as female.

- 41% of respondents self-identified as male.

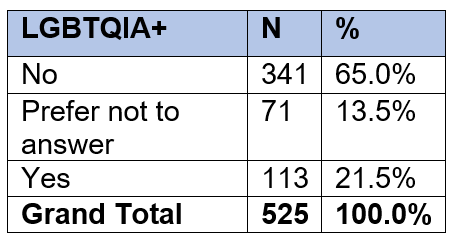

LGBTQIA+ identity:

- 22% of respondents identified as members of the LGBTQIA+ community.

Age:

- The average age of respondents was 45 years.

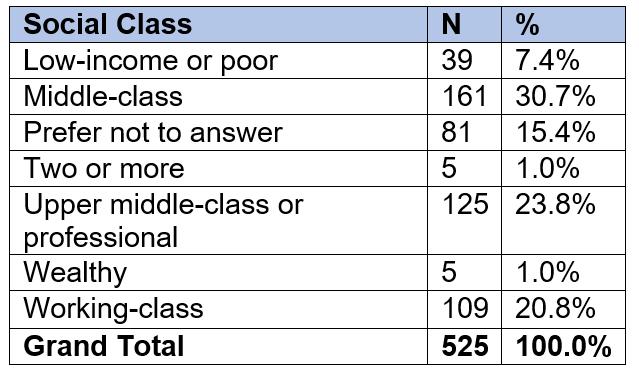

Social class:

- 55% of respondents identified as middle class or upper middle-class.

- 7% of respondents identified as low-income or poor.

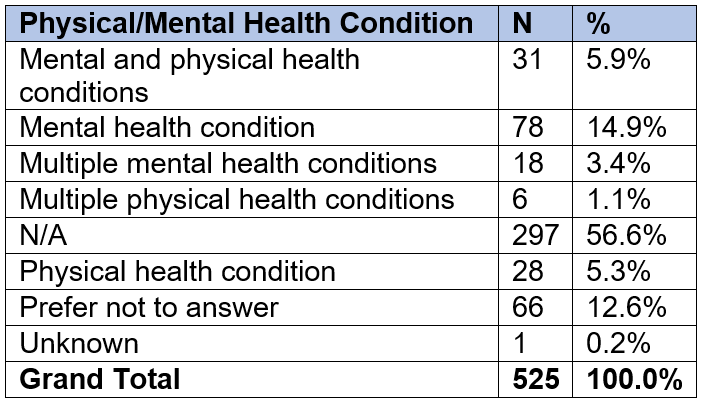

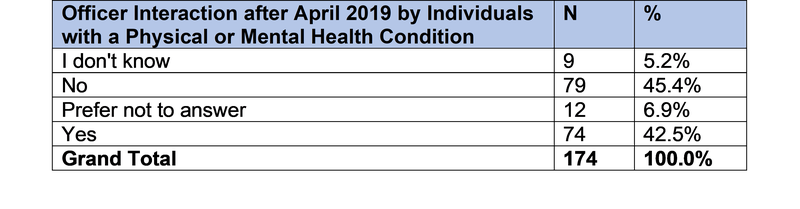

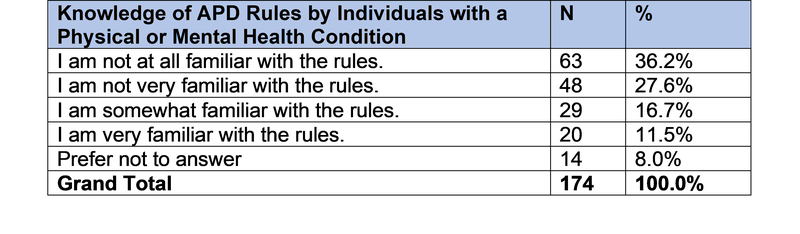

Physical and mental health conditions:

- 33% of respondents reported having a physical or mental health condition.

- Of the respondents who identified as having a physical or mental health condition, 73% of respondents reported having one or more mental health conditions.

- Of the respondents who identified as having a physical or mental health condition, 18% of respondents reported having both a mental and physical health condition.

Residential and employment ZIP codes:

- The largest percentage of survey respondents (9%) reported living in the 78745 ZIP code (Southwest Austin).

- The largest percentage of survey respondents (15%) reported working in the 78701 ZIP code (Central Austin).

Map of Austin showing ZIP codes and council districts. (Source: City of Austin Housing and Planning Department).

Data Analysis Discussion and Findings 4 of 7

Interactions with Officers and Knowledge of Body-Worn and Dashboard Camera Rules

In addition to sentiment and demographic data, OPO collected and analyzed data on respondents’ interactions with APD officers and knowledge of APD’s current body-worn and dashboard camera policies. Details of this analysis are provided below.

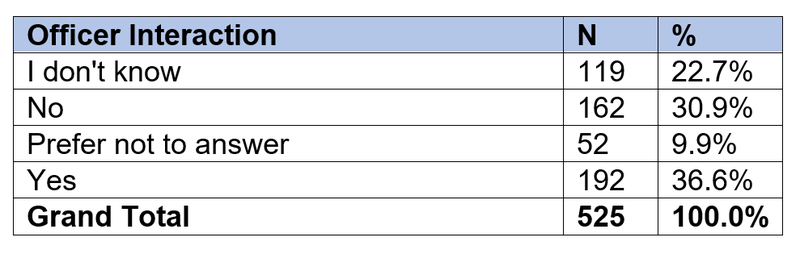

Past interactions with an on-duty APD officer wearing a body-worn camera:

- 37% of respondents reported having had an interaction with an on-duty APD officer wearing a body-worn camera.

- 31% of respondents said they had not ever had such an interaction.

- 23% of respondents reported not knowing whether they had ever had such an interaction.

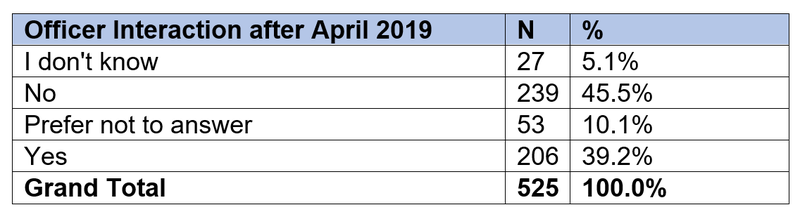

Past interactions with an on-duty APD officer after April 2019 [4]:

- 46% of respondents said they had no interaction with an APD officer after April 2019.

- Of the respondents who said they had an interaction with an APD officer after April 2019, 36% said they had a physical or mental health condition.

Knowledge of recording during interaction with APD officer:

- 25% of respondents believe they were recorded by an APD officer.

- Of the respondents who provided details about their experience being recorded by an APD officer [5], 78% believed the interaction was recorded by a body-worn camera because they saw the officer wearing the body-worn camera.

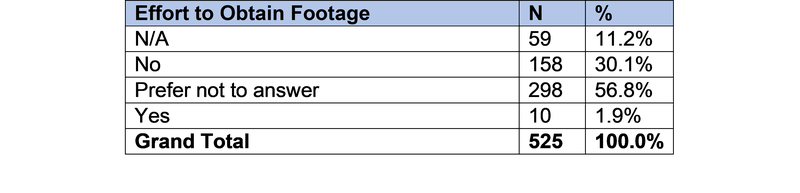

Effort to obtain footage:

- Only a small percentage of respondents (2%) said they attempted to get access to video footage capturing a past interaction with an on-duty APD officer.

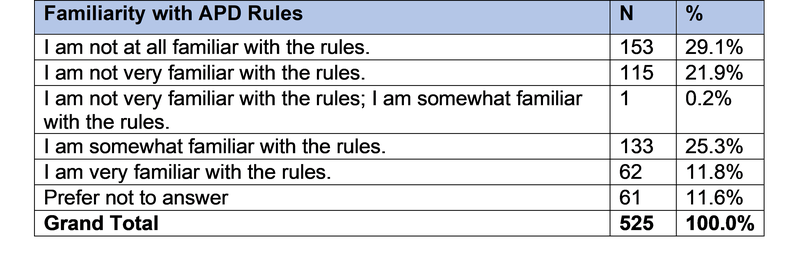

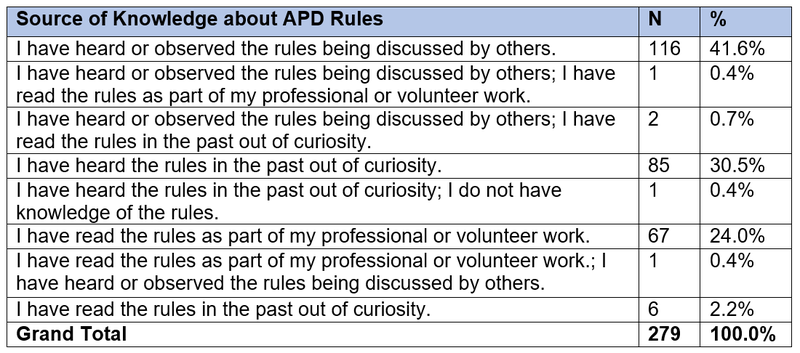

Knowledge and source of knowledge of APD’s body-worn and dashboard camera policies:

- 29% of respondents indicated that they were not at all familiar with APD’s body-worn and dashboard camera rules.

- Of the respondents who provided a substantive response [6] and confirmed some level of knowledge regarding APD’s body-worn and dashboard camera rules, 42% indicated that they learned about the policies because they heard or observed them being discussed by others.

- Of respondents who said that they live with a mental or physical condition, 36% said they are not at all familiar with APD’s rules related to body-worn and dashboard cameras.

Data Analysis Discussion and Findings 5 of 7

Comparison Between Paper & Digital Survey Submissions

Paper surveys had a higher percentage of respondents who were supportive of OPO’s recommendations.

The table linked below outlines this finding with a side-by-side comparison of percentages of favorable paper and digital survey responses for the sentiment questions asked on OPO’s survey.

The remaining percentage of responses were either not in favor of OPO’s recommendations, preferred not to answer, or did not have an opinion.

View (PDF, 151 KB) the comparison of sentiments expressed in paper versus digital surveys.

View (PDF, 195 KB) a copy of our survey in English.

Data Analysis Discussion and Findings 6 of 7

Glossary and Additional Information

Below are the sources and additional information for Data Analysis Discussion and Findings.

For More Information

View a glossary of terms used in the data analysis discussion.

Learn more about our methodology and how we cleaned our data.

Data Analysis Discussion and Findings 7 of 7

Endnotes

Below are the endnotes for the Data Analysis Discussion and Findings section.

[1] See e.g. National Center on Disability and Journalism, “Disability Language Style Guide,” last modified August 2021, https://ncdj.org/style-guide/#A; Denver Prevention Training Center and Denver Health LGBT Health Services, “Guide to LGBTQ+ Inclusive Forms,” accessed December 8, 2021. Inclusive Forms 2019-03-24 for Remediation_R.pdf (PDF, 626 KB).

[2] Lila Valencia (City Demographer) in discussion with OPO, December 2021.

[3] For purposes of this analysis, this term includes those respondents who self-identified as Two Spirit, Non-binary/Genderqueer/Gender-fluid, and/or Transgender Woman/Trans Feminine.

[4] See City of Austin Office of the City Auditor, Austin Police Department Body-Worn Cameras, June 2019, accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Auditor/Audit_Reports/APD_Body-Worn_Camera_Program_June_2019.pdf (PDF, 1.1 MB). (Per a report by the City Auditor, all APD officers except for chiefs and commanders were equipped with a body-worn camera system by April 2019. Thus, community members who interacted with an on-duty APD officer after April 2019 likely interacted with an officer equipped with a body-worn camera.)

[5] This population includes any respondent who indicated knowledge of being recorded by an APD officer or provided details regarding how they knew they were being recorded by an APD officer.

[6] For purposes of this analysis, “prefer not to answer” does not constitute a substantive response.

[7] OPO tabled at the following Austin Public Library branches: Central, Little Walnut Creek, Willie Mae Kirk, Menchaca Road, Pleasant Hills, Southeast, Windsor Park, and Ruiz. OPO also worked with the Austin Public Library to distribute surveys in English and Spanish to all branches and received 18 surveys that were bundled by Austin Public Library staff and could not be tied to specific library branches.

[8] OPO tabled at the Gus Garcia Recreation Center twice, on March 23 and March 30. A total of 7 paper surveys were filled out by residents.

[9] OPO tabled at the Pop-Up Resource Clinic (PURC) organized and run by the City of Austin's Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Department. EMS works with partners to provide several services including health check-ups, basic necessities, and referrals to care providers and nonprofits to people experiencing homelessness at rotating locations across the city. OPO attended the PURC at Oak Meadow Baptist on March 23, 2022 and received a total of 6 paper surveys.

[10] For ease of understanding during Phase II, OPO compiled two issues from Phase I into this broader topic. The issues in Phase I were as follows: (1) unclear concepts and definitions related to recording and (2) officer discretion in determining when to record.

[11] The City of Austin contracts with a web-based survey platform called Public Input. Many City departments utilize Public Input to host their digital surveys. OPO utilized the City’s Public Input account to host the digital survey for this project. Several issues arose with the collection and storage of information by Public Input. For example, the platform allowed respondents to skip questions that were meant to be required, and it stored incomplete or abandoned surveys but provided no mechanism for identifying whether the survey was truly abandoned.

The Role of Vendors & Community Input in Policy Development

The Role of Vendors & Community Input in Policy Development 1 of 5

Introduction

In Phase I of this project, OPO examined whether APD’s current body-worn and dashboard camera policies aligned with best practices, relevant laws, and the City of Austin’s policies, goals, and values.

OPO discussed key findings from Phase I in a report published in January 2022.[1] One of the main issues discussed in the report was the role of private vendors and community voices in APD’s policymaking process. The pages that follow revisit that topic, discussing key findings from OPO’s research into the policymaking practices of 15 other U.S. police departments, insights from feedback provided by Austin community members, and final policy recommendations as to the role of vendors and community input in the policymaking process.

Takeaways

1. Community input is necessary to improve policy, but feedback needs to be obtained intentionally.

Austin community members indicated a desire for more engagement opportunities and different engagement opportunities. Responses suggest a need to utilize new processes to engage the people who are most impacted by APD policies and involve those people from the very beginning.

2. None of the responding cities use vendors for policy writing.

OPO asked police departments and oversight bodies from 15 cities across the country about their use of vendors for policy writing and eight cities responded. None of these eight cities currently contract with vendors to write policy. The eight responding cities were as follows:

- Baltimore

- Charlotte

- Dallas

- Denver

- Fort Worth

- Portland

- San Antonio

- San Francisco

3. Vendor policies may indirectly impact cities that keep their policymaking processes in-house.

While the majority of the 15 cities do not contract with vendors to write policy, several said that they examine other police departments’ policies when researching best practices. This process may lead to vendors having an indirect impact on the policies of departments that intentionally avoid contracting with vendors.

4. Police departments use a range of methods to collect community input, and the departments with more structured processes take a multi-faceted approach that includes opportunities for both a broad response and a more focused response.

Some police departments, like the Denver Police Department and Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department, collect community input periodically based on the nature of the policy at issue.[2] Other police departments, like the San Francisco Police Department and the Portland Police Bureau, seek community feedback regularly as an established part of the policymaking process.[3] San Francisco and Portland both require periods of public comment as part of the review process for most policies, and both also seek input from subject matter experts, advisory groups, and/or working groups.[4]

5. Some oversight entities redirected questions about policymaking to their city’s police department, citing a lack of detailed information.

This may suggest that current policymaking processes in these police departments lack transparency or that oversight bodies in these cities are not directly and routinely involved in the police department’s policymaking processes.

The Role of Vendors & Community Input in Policy Development 2 of 5

Discussion of 15-City Survey: Policymaking Processes Utilized by Other U.S. Police Departments.

The following is a discussion of policymaking processes utilized by other U.S. police departments.

In Phase I, OPO discussed APD’s ongoing contract with Lexipol—a private company that, among other things, provides services related to policy writing.[5] As outlined in the Phase I report, Lexipol prioritizes risk management for police departments and advertises itself as a way for police departments to decrease liability in civil suits alleging police misconduct.[6] This approach, however, does not necessarily result in policies that ensure accountability or reflect local community input.[7]

In Phase III, OPO wanted to learn whether comparable cities contract with Lexipol or other vendors to draft police policy, and the extent to which the police departments in these cities engage with the community as part of their policymaking processes. As a result, OPO reached out to police departments and oversight bodies in 15 cities across the country. OPO received responses from 8 cities, including:

- Baltimore

- Charlotte

- Dallas

- Denver

- Fort Worth

- Portland

- San Antonio

- San Francisco

For the 7 cities that did not provide a response, OPO conducted additional desk research to attempt to answer these questions. What follows are key findings from this 15-city survey:

1.None of the responding cities use vendors for policy writing.

OPO asked police departments and oversight bodies from 15 cities across the country about their use of vendors for policy writing and eight cities responded. None of these eight cities currently contract with vendors to write policy. The eight responding cities were as follows:

- Baltimore

- Charlotte

- Dallas

- Denver

- Fort Worth

- Portland

- San Antonio

- San Francisco

OPO conducted desk research on the seven other cities and did not find any information about whether they currently contract with vendors for policy writing. The seven other cities were as follows:

- Atlanta

- Houston

- Memphis

- New Orleans

- San Diego

- San José

- Seattle

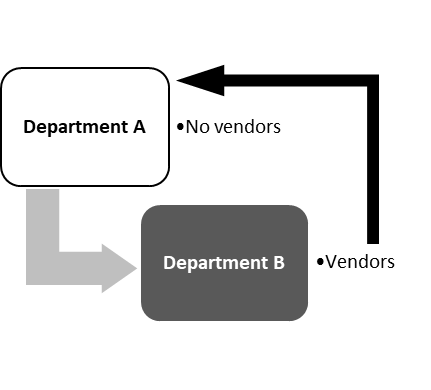

- Vendor policies may indirectly impact cities that keep their policymaking processes in-house.

None of the responding cities currently contract with vendors to write policy, but several stated that they do things like:

- Solicit feedback from experts;

- Look at recommendations made by leading policing organizations; and

- Research policies and best practices of other police departments across the country.

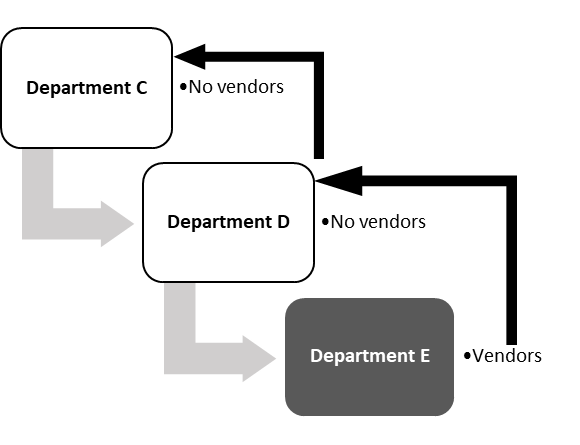

These practices are an established part of best practices research, but they make it nearly impossible to determine the degree to which vendors have input on police policy. Vendors can influence policy language even if they do not directly contract with a specific department. Consider the following scenarios:

- Department A does not contract with a vendor to write its policies. However, Department A examines Department B’s policies as part of its best practices research. Department B contracts with a vendor. Department A’s policies may be impacted by vendor-created language in Department B’s policies.

- Department C does not contract with a vendor to write its policies. However, Department C examines Department D’s policies as part of its best practices research. Department D does not contract with a vendor, but it does examine Department E’s policies. Department E contracts with a vendor. Department D’s policies may be impacted by vendor-created language and then impact Department C’s policies.

As these scenarios demonstrate, a vendor’s influence may reach beyond the contracting department. For example, a department that intentionally avoids policy vendors may end up unintentionally using vendor language based on the nature of their research process. OPO is aware of no comprehensive list of departments that contract with vendors to create policy, and research processes vary widely from department to department.

For example, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department reported examining specific cities that are relatively similar in population and department size.[8] On the other hand, the Baltimore Police Department reported reviewing various departments’ policies and best practices depending on the topic and recommendations made by stakeholders.[9]

Two cities (Baltimore and New Orleans) previously contracted with Lexipol for policy services.[10] Baltimore terminated their contract early as the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) came under a pattern-or-practice investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice.[11] BPD has since secured staffing to support in-house policy development.[12] No policies developed by Lexipol were ever published by BPD.[13] New Orleans came under a pattern-or-practice investigation in May 2010,[14] and entered into a consent decree in January 2013.[15] New Orleans first contracted with Lexipol in December 2011 and extended their initial contract with Lexipol twice until 2014.[16]

Given the lack of response from New Orleans, OPO was unable to determine the extent to which the New Orleans Police Department utilized policies crafted by Lexipol.

In 2019, Lexipol reported providing policies to over 3,500 agencies.[17] Given this large number, it is impossible to ascertain whether Lexipol had a secondary impact on the police department policies of the 15 cities OPO surveyed. OPO was also unable to determine whether vendors other than Lexipol had a secondary impact. Nevertheless, the information that OPO did gather demonstrates that police departments appear to be able to keep up with current laws and draft comprehensive policies without relying on vendors.

3. Police departments use a range of methods to research best practices and collect community input, and the departments with more structured processes for community input take a multi-faceted approach that includes opportunities for both a broad response and a more focused response.

Approaches for collecting community feedback varied from department to department, differing both in frequency and process. For example:

- The Portland Police Bureau implemented a policy that requires it to regularly solicit community input and involves two public comment periods—one (15 days) for current language and another (30 days) for proposed changes made after meeting with subject matter experts and reviewing the initial public comments.[18]

- The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department only seeks community feedback in rare instances (e.g., revising its use-of-force policy after a 2019 officer-involved shooting).[19]

- The Denver Police Department solicits community feedback on policies that are considered major issues that impact community relations (e.g., policing technologies and the use of force).[20] In contrast, policies that are considered administrative in nature may only have input from other internal actors like elected officials and the city attorney’s office.[21]

- The San Francisco Police Department is implementing a policy that will require a 30-day comment period as part of the review process for most General Orders revisions.[22] Previously, the comment period was 10 days and community members had to present their feedback at a public meeting of the Police Commission.[23] The current process seeks feedback from community by directly involving external stakeholders through working groups dedicated to specific policies and significant collaboration with San Francisco’s civilian oversight office.[24]

- The City of Atlanta partnered with the Police Executive Research Forum and an Atlanta-based consulting firm in 2020 to assess the Atlanta Police Department’s policies and practices and gather community input.[25] The consulting firm unit engaged police, subject matter experts, and residents through town halls, focus groups, and surveys.[26] This resulted in a report with 150 recommendations, and a dashboard to track the implementation of recommendations that were approved.[27]

The way in which departments solicit community feedback also varied. Police departments’ processes usually included one or a combination of the following methods:

- Written response through email or an online portal;

- Partnering with external stakeholders (e.g., advocates and non-profit organizations);

- Organizing and overseeing working groups;

- Working with elected or appointed officials (e.g., mayors and public safety committee members); and

- Public community meetings or town hall events.

- Many oversight entities redirected questions about policymaking to their city’s police department, often citing a lack of detailed information.

OPO first contacted each of the 15 cities by reaching out to each city’s civilian oversight body. In many cases, the civilian oversight body redirected OPO to someone within the city’s police department, citing a lack of detailed information. This may suggest that current policymaking processes in these police departments lack transparency or that oversight bodies in these cities are not directly and routinely involved in the police departments’ policymaking processes.

The following table provides an overview of the information from each of the 15 cities, including the extent to which they utilize community input and vendors in crafting police department policy.

The Role of Vendors & Community Input in Policy Development 3 of 5

Discussion of Community Feedback

Through surveys and virtual events, OPO sought feedback from Austin community members on APD’s current use of policy vendors and community input, as well as OPO’s recommendations.

The following was the key insight from community voices at OPO’s virtual events:

Community input is necessary to improve policy, but feedback needs to be obtained intentionally.

In addition to supporting community input in policymaking, responses from those attending OPO’s virtual events also suggest a need for engagement that focuses on people who are most impacted and involves those people from the very beginning.

Below are comments (made verbally or in writing) from community members who attended OPO’s virtual events:

- “Policies should align with what the community wants. This means reaching over-policed populations especially District 1-4."

- “I suggest that it would vary depending on the policy that we’re talking about. So, for example, the body camera policy has a couple of different sections. There’s a section specific to critical incidents and I think that the policy related to the release of body camera video when a person’s family member has been killed--I’m sorry it’s hard to say this in a minute--has things you need to account for. So, I think that it’s important for crafting a good release of body camera videos for critical incidents including families of people who have had family members killed by police. I think that their input about how and when that release should roll out and when things should be available to the public when these incidents are very triggering kind of is a special case. But then there’s all the other body camera video that relates to really, like, the day to day, and I think a much broader public can all have important views on when that should be released.”

- “I agree with the recommendations as well, but I was wondering when in terms of community input, having the community be a part of the crafting of the policy changes. Here you’ve crafted it and now you’re asking for our input after the fact. Maybe having the community as a part of the conversations to begin with.”

- “All policies should be open to community input. The APD exists to serve us.”

Data from OPO’s community-wide survey shows that people believe community input should be a part of the policymaking process and that community involvement makes the government more accountable.

- 66% of respondents believe that community involvement positively impacts government accountability.

- 66% of respondents believe the City should request and use public feedback when writing rules.

- 61% of respondents would like the City's body-worn camera and dashboard camera program to include more community input.

The Role of Vendors & Community Input in Policy Development 4 of 5

Glossary and Additional Information

For more information:

View a glossary of terms used in this section here.

Learn more about our methodology here.

View (PDF, 283 KB) additional information collected in our 15-city survey here.

The Role of Vendors & Community Input in Policy Development 5 of 5

Endnotes

Below are endnotes for the Role of Vendors & Community Input in Policy Development section.

[1] City of Austin Office of Police Oversight, Body-Worn Cameras & Dashboard Cameras: Policy Review and Recommendations, January 27, 2022, https://www.austintexas.gov/document/body-worn-cameras-and-dashboard-cameras-policy-review-and-recommendations

[2] Daniel White (Management Analyst III, Planning Research & Support Section, Denver Police Department), email message to OPO, April 25, 2022; Sandy D’Elosua Vastola (Staff, Office of the Chief, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department), email message to OPO, May 10, 2022.

[3] M. Catherine McGuire (Executive Director, Strategic Management Bureau, San Francisco Police Department) in discussion with OPO, June 20, 2022; Ashley Lancaster (Policy Director, Policy Development Team, Training Division, Portland Police Bureau), email message to OPO, May 9, 2022.

[4] See endnote 3.

[5] City of Austin Office of Police Oversight, Body-Worn Cameras and Dashboard Cameras: Policy Review and Recommendations, January 27, 2022, https://www.austintexas.gov/document/body-worn-cameras-and-dashboard-cameras-policy-review-and-recommendations; see Eagley, Ingrid V. and Joanna C. Schwartz, 2017, “Lexipol The Privatization of Police Policymaking,” Texas Law Review 96(5): 891-976, accessed July 27, 2022, https://texaslawreview.org/lexipol/.

[6] Eagley, Ingrid V. and Joanna C. Schwartz, 2017, “Lexipol: The Privatization of Police Policymaking,” Texas Law Review 96(5): 891-976, accessed July 27, 2022, https://texaslawreview.org/lexipol/.

[7] See endnote 6.

[8] Sandy D’Elosua Vastola (Staff, Office of the Chief, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department), email message to OPO, May 10, 2022 (stating that the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department sources policies from comparable cities that are relatively similar in population and department size, including Baltimore, Atlanta, Memphis, Nashville, Louisville Metro and Columbus).

[9] Lisa Fink (Policy Specialist/Language Access Coordinator, Baltimore Police Department), email message to OPO, May 9, 2022 (stating that the Baltimore Police Department accesses policies through IACPnet and other listservs).

[10] Shannon Sullivan (Director, Consent Decree Implementation Unit, Baltimore Police Department), email message to OPO, June 15, 2022; City of New Orleans, “Professional Services Agreement Between the City of New Orleans and Lexipol LLC,” December 9, 2011, Professional Services Agreement Between the City of New Orleans and Lexipol LLC.pdf; City of New Orleans, “Amendment No. 1 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, L.L.C NOPD Web-Based Policy Content,” March 19, 2013, Amendment No. 1 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, LLC NOPD Web-Based Policy Content; City of New Orleans, “Amendment No. 2 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, L.L.C NOPD Web-Based Policy Content,” January 22, 2022, Amendment of No.2 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol,LLC NOPD WEb-Based Policy Content.

[11] Shannon Sullivan (Director, Consent Decree Implementation Unit, Baltimore Police Department), email message to OPO, June 15, 2022.

[12] Shannon Sullivan (Director, Consent Decree Implementation Unit, Baltimore Police Department), in discussion with OPO, June 15, 2022.

[13] See endnotes 11 and 12.

[14] “FAQ,” New Orleans Police Department Consent Decree Monitor, accessed July 27, 2022, http://consentdecreemonitor.com/faq.

[15] “Welcome,” New Orleans Police Department Consent Decree Monitor, accessed July 27, 2022, http://consentdecreemonitor.com/.

[16] City of New Orleans, “Professional Services Agreement Between the City of New Orleans and Lexipol LLC,” December 9, 2011, Professional Services Agreement Between The City of Orleans and Lexipol LLC; City of New Orleans, “Amendment No. 1 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, L.L.C NOPD Web-Based Policy Content,” March 19, 2013, Amendment No.1 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, LLC NOPD WEb- Based Policy Content; City of New Orleans, “Amendment No. 2 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, L.L.C NOPD Web-Based Policy Content,” January 22, 2022,Amendment No.2 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, LLC NOPD Web-Based Policy.

[17] “Lexipol and Public Employer Risk Management Association Announce Partnership Providing Law Enforcement Policies and Training,” Lexipol LLC, September 12, 2019, https://www.lexipol.com/lexipol-and-perma-announce-partnership-providing-law-enforcement-policies-and-training/.

[18] Ashley Lancaster (Policy Director, Policy Development Team, Training Division, Portland Police Bureau), email message to OPO, May 9, 2022; Portland Police Bureau, “0010.00 Directives Review and Development Process,” Portland Police Bureau Directives Manual, March 30, 2018, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/police/article/678287.

[19] Sandy D’Elosua Vastola (Staff, Office of the Chief, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department), email message to OPO, May 5, 2022

[20] Daniel White (Management Analyst III, Planning Research & Support Section, Denver Police Department), email message to OPO, April 25, 2022.

[21] See endnote 20.

[22] Janelle Caywood (Director of Policy, San Francisco Department of Police Accountability), email message to OPO, May 2, 2022.

[23] See endnote 22.

[24] M. Catherine McGuire (Executive Director, Strategic Management Bureau, San Francisco Police Department) in discussion with OPO, June 20, 2022; Janelle Caywood (Director of Policy, San Francisco Department of Police Accountability), email message to OPO, May 2, 2022.

[25] Police Executive Research Forum, “Atlanta Police Department: Agency Review and Assessment,” April 2022, Atlanta Police Department Agency Review and Assessment.pdf.

[26] City of Atlanta, “The Police Executive Research Forum and APD Urban Planning and Management Provide the Atlanta Police Department with Approximately 150 Policy and Practice Recommendations,” accessed July 12, 2022, https://justicereform.atlantaga.gov/police-reform.

[27] See endnote 26.

[28] A “desk research” designation has been applied to cities that did not respond to OPO’s inquiries. For these cities, OPO’s desk research focused on locating other primary sources for the requested information. Most sources were gathered from city department websites (e.g., finance, procurement, police department, consent decree monitor). In some cases, OPO also looked to policing organizations, like the Police Executive Research Forum, that published research gathered through direct contact with the department(s) at issue.

[29] A “contact” designation has been applied to cities that responded directly to OPO’s inquiries.

[30] A “hybrid” designation has been applied to cities that responded to OPO’s inquiries and for which OPO completed supplemental desk research.

[31] “Consent Decree Basics,” Baltimore Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.baltimorepolice.org/transparency/consent-decree-basics; “NOPD Consent Decree,” New Orleans Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.nola.gov/nopd/nopd-consent-decree/; “DOJ Settlement,” Portland Police Bureau, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.portland.gov/police/doj; “Settlement Agreement History,” Seattle Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.seattle.gov/police/about-us/professional-standards-bureau/settlement-agreement-history.

[32] “Justice Department Releases Critical Response Report of San Diego Police Department’s Misconduct Policies and Practices,” The United States Department of Justice, March 17, 2015, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-releases-critical-response-report-san-diego-police-departments-misconduct.

[33] “CRI Timeline,” San Francisco Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/your-sfpd/police-reform/cri-timeline.

[34] See endnote 33.

[35] M. Catherine McGuire (Executive Director, Strategic Management Bureau, San Francisco Police Department) in discussion with OPO, June 20, 2022.

[36] Police Executive Research Forum, “Atlanta Police Department: Agency Review and Assessment,” April 2022, Atlanta Police Department Agency Review and Assessment.pdf.

[37] City of Atlanta, “The Police Executive Research Forum and APD Urban Planning and Management Provide the Atlanta Police Department with Approximately 150 Policy and Practice Recommendations,” accessed July 12, 2022, https://justicereform.atlantaga.gov/police-reform.

[38] See endnote 37.

[39] APD Urban Planning and Management, LLC, “2022 Community Survey Extension,” May 19, 2022, https://www.atlantaga.gov/home/showdocument?id=55573open_in_new.

[40] Atlanta Police Department, “Written Directive 4.1.2 Review Process,” Atlanta Police Department Written Directives, accessed July 26, 2022, https://www.atlantapd.org/about-apd/standard-operating-procedures/-folder-57.

[41] See endnote 40.

[42] Lisa Fink (Policy Specialist/Language Access Coordinator, Baltimore Police Department), email message to OPO, May 9, 2022.

[43] Shannon Sullivan (Director, Consent Decree Implementation Unit, Baltimore Police Department), email message to OPO, June 15, 2022.

[44] See endnote 43.

[45] See endnote 43.

[46] Lisa Fink (Policy Specialist/Language Access Coordinator, Baltimore Police Department), email message to OPO, May 9, 2022.

[47] See endnote 46.

[48] See endnote 46; “Consent Decree Basics,” Baltimore Police Department, accessed July 25, 2022, https://www.baltimorepolice.org/transparency/consent-decree-basics.

[49] See endnote 46.

[50] See endnote 46.

[51] See endnote 46.

[52] See endnote 46.

[53] See endnote 46.

[54] See endnote 46.

[55] See endnote 46.

[56] Sandy D’Elosua Vastola (Staff, Office of the Chief, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department), email message to OPO, May 5, 2022.

[57] See endnote 56.

[58] See endnote 56.

[59] See endnote 56.

[60] See endnote 56.

[61] Nicole Jackson (Administrative Specialist II), email message to OPO, July 22, 2022.

[62] “Vendor Payments,” City of Dallas, accessed June 10, 2022, http://spending.dallasopendata.com/#!/year/All%20Years/explore/0-/vendor/Lexipol,+LLC/1-AD-BMS-AY220017181/fundtype (other line items are for other City of Dallas departments, such as courts and detention services).

[63] Nicole Jackson (Administrative Specialist II, Dallas Police Department), email message to OPO, July 22, 2022; Ernest Lampkin (Contracts Manager) in discussion with OPO, July 14, 2022.

[64] Ernest Lampkin (Contracts Manager, Dallas Police Department) in discussion with OPO, July 14, 2022.

[65] See endnote 61.

[66] Daniel White (Management Analyst III, Planning Research & Support Section, Denver Police Department), email message to OPO, April 25, 2022.

[67] See endnote 66.

[68] See endnote 66.

[69] See endnote 66.

[70] Margaret Humphrey (Policy Analyst/Advanced Certified Police Planner/Texas Accreditation Program Manager, Fort Worth Police Department), email message to OPO, April 27, 2022.

[71] See endnote 70.

[72] See endnote 70.

[73] See endnote 70.

[74] Houston Police Department, “General Order 100-01 Internal Directives,” Houston Police Department General Orders, accessed July 26, 2022, https://www.houstontx.gov/police/general_orders/index.htm.

[75] City of Houston, "City of Houston Mayor’s Task Force on Policing Reform," September 2020, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.houstontx.gov/boards/policing-reform-report.pdf.

[76] See endnote 75.

[77] “Citizens and Police…Friendship Through Education,” Houston Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.houstontx.gov/police/pip/.

[78] See endnote 77.

[79] See endnote 77.

[80] Memphis Police Department, “Chapter I, Section 1, Part IV(A)(7)(b),” Memphis Police Department Policies & Procedures, accessed July 26, 2022, https://memphispolice.org/policies-and-procedures/.

[81] Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice, “The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing Implementation Guide: Moving from Recommendations to Action,” 2015, accessed July 27, 2022, https://cops.usdoj.gov/RIC/Publications/cops-p341-pub.pdf.

[82] City of Memphis, “Reimagine Policing in Memphis: Pillar One,” accessed July 27, 2022, https://reimagine.memphistn.gov/21st-century-policing/pillar-one/.

[83] City of Memphis, “Reimagine Policing in Memphis: Pillar Two,” accessed July 27, 2022, https://reimagine.memphistn.gov/21st-century-policing/pillar-two/.

[84] City of Memphis, “Reimagine Policing in Memphis: Pillar Four,” accessed July 27, 2022, https://reimagine.memphistn.gov/21st-century-policing/pillar-four/.

[85] See endnote 84.

[86] “Contract Search,” City of New Orleans, accessed June 10, 2022, https://contracts.nola.gov/.

[87] City of New Orleans, “Professional Services Agreement Between the City of New Orleans and Lexipol LLC,” December 9, 2011, https://contracts.nola.gov/nola_svc/api/document/98761 (entered into 12/9/11 with effective date of 12/13/11).

[88] City of New Orleans, “Amendment No. 1 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, L.L.C NOPD Web-Based Policy Content,” March 19, 2013, https://contracts.nola.gov/nola_svc/api/document/99018 (entered into 3/19/13 with effective date 12/14/12); City of New Orleans, “Amendment No. 2 to Professional Services Agreement Between City of New Orleans and Lexipol, L.L.C NOPD Web-Based Policy Content,” January 22, 2022, https://contracts.nola.gov/nola_svc/api/document/99204 (entered into 1/22/14 with effective date 12/14/13).

[89] See New Orleans Police Department, “New Orleans Police Department Operation Manual,” https://www.nola.gov/nopd/policies/, accessed June 15, 2022.

[90] New Orleans Police Department, “Chapter 10.0: Community Policing and Engagement,” New Orleans Police Department Operation Manual, October 2021, accessed July 12, 2022, https://nola.gov/getattachment/NOPD/Policies/Chapter-10-0-Community-Policing-and-Engagement-EFFECTIVE-10-10-21.pdf/?lang=en-US.

[91] “FAQ,” New Orleans Police Department Consent Decree Monitor, accessed July 12, 2022, http://consentdecreemonitor.com/faq.

[92] See endnote 91.

[93] See endnote 91.

[94] “Community Involvement,” New Orleans Police Department Consent Decree Monitor, accessed July 12, 2022, http://consentdecreemonitor.com/community-involvement.

[95] “Schedule,” New Orleans Consent Decree Monitor, accessed July 12, 2022, http://consentdecreemonitor.com/schedule.

[96] See endnote 94.

[97] Ashley Lancaster (Policy Director, Policy Development Team, Training Division, Portland Police Bureau), email message to OPO, May 9, 2022.

[98] See endnote 97.

[99] See endnote 97.

[100] See endnote 97.

[101] Portland Police Bureau, “Portland Police Bureau Department of Justice Progress Report,” March 2014, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/police/article/488469 (stating that the Portland City Council approved the settlement agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice in 2012).

[102] See endnote 97.

[103] See endnote 97.

[104] See endnote 97.

[105] See endnote 97.

[106] See endnote 97; see also Portland Police Bureau, “Directive 0010.00 Directives Review and Development Process,” Portland Police Bureau Directives Manual, accessed May 10, 2022, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/police/article/678287.

[107] See endnote 97.

[108] See endnote 97.

[109] Washington Moscoso (Police Media Services Supervisor, San Antonio Police Department), email message to OPO, May 6, 2022.

[110] See endnote 109.

[111] See endnote 109.

[112] See endnote 109.

[113] See endnote 109.

[114] See endnote 109.

[115] “Policies and Procedures,” San Diego Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sandiego.gov/police/data-transparency/policies-procedures (stating, “On occasion, certain draft procedures will be made available for public comment.”).

[116] “Public Comment for SDPD Procedures,” San Diego Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sandiego.gov/police/data-transparency/public-comment-draft-procedures.

[117] See endnote 116.

[118] “Zencity Trust and Safety Survey,” San Diego Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sandiego.gov/police/data-transparency/trust-safety-survey.

[119] See endnote 118.

[120] M. Catherine McGuire (Executive Director, Strategic Management Bureau, San Francisco Police Department) in discussion with OPO, June 20, 2022.

[121] “CRI Timeline,” San Francisco Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sanfranciscopolice.org/your-sfpd/police-reform/cri-timeline.

[122] M. Catherine McGuire (Executive Director, Strategic Management Bureau, San Francisco Police Department) in discussion with OPO, June 20, 2022.

[123] Janelle Caywood (Director of Policy, San Francisco Department of Police Accountability), email message to OPO, May 2, 2022.

[124] See endnote 123.

[125] M. Catherine McGuire (Executive Director, Strategic Management Bureau, San Francisco Police Department), email message to OPO, June 16, 2022.

[126] See endnote 123.

[127] See endnote 123.

[128] See endnote 125.

[129] See endnote 125.

[130] See endnote 125.

[131] See endnote 125; M. Catherine McGuire (Executive Director, Strategic Management Bureau, San Francisco Police Department) in discussion with OPO, June 20, 2022 (the grid is used in lieu of redlining to try to ensure that the General Orders have a consistent voice).

[132] See endnote 125.

[133] See endnote 125; M. Catherine McGuire (Executive Director, Strategic Management Bureau, San Francisco Police Department) in discussion with OPO, June 20, 2022 (SFPD tries to ensure that working groups are made up of between 6-10 members).

[134] See endnote 125.

[135] Janelle Caywood (Director of Policy, San Francisco Department of Police Accountability), email message to OPO, May 2, 2022.

[136] “Community Surveys,” San José Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sjpd.org/community/community-services/community-surveys.

[137] See endnote 136.

[138] See endnote 136.

[139] See “Body Camera Information,” San José Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sjpd.org/about-us/inside-sjpd/body-camera-information; SANJOSEPOLICE, “Body Worn Camera Public Rollout,” San José Police Department, October 26, 2015, video, 1:49, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jzw1ZUITp0Q&t=26s.

[140] SANJOSEPOLICE, “Body Worn Camera Public Rollout,” San José Police Department, October 26, 2015, video, 1:49, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jzw1ZUITp0Q&t=26s.

[141] “Body Camera Information,” San José Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sjpd.org/about-us/inside-sjpd/body-camera-information.

[142] “21st Century Policing,” San José Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sjpd.org/about-us/organization/office-of-the-chief-of-police/21st-century-policing.

[143] “LGBTQ Community Liaison,” San José Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sjpd.org/about-us/organization/office-of-the-chief-of-police/lgbtq-community-liaison.

[144] “Community Advisory Board,” San José Police Department, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sjpd.org/about-us/organization/office-of-the-chief-of-police/community-advisory-board.

[145] “News Release Correction: San José Hires Independent Experts to Review the Police Department’s Use of Force and Other Policies,” City of San José, accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.sanjoseca.gov/Home/Components/News/News/3002/4699.

[146] See endnote 145.

[147] “Frequently Asked Questions,” Seattle Police Monitor, accessed July 12, 2022. https://seattlepolicemonitor.org/faq.

[148] See endnote 147.

[149] See endnote 147.

[150] “Comprehensive Assessment of the Seattle Police Department,” Seattle Police Monitor, May 2022, https://seattlepolicemonitor.org/sites/default/files/2022-05/Seattle_Police_Monitor_Comprehensive_Assessment.pdf.

[151] See endnote 150.

[152] “Frequently Asked Questions,” Seattle Police Monitor, accessed July 12, 2022. https://seattlepolicemonitor.org/faq.

[153] See endnote 152.

[154] “Community Police Commission,” City of Seattle, accessed July 12, 2022, https://www.seattle.gov/community-police-commission/about-us#commissioners.

[155] United States v. City of Seattle, Civil Action No. 12-CV- 1282 (W.D. Wash July 27, 2012), https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/Police/Compliance/Consent_Decree.pdf.

[156] Ordinance 125312 Council Bill 118969, Seattle City Council (June 1, 2017), accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/CommunityPoliceCommission/Ordinance_APPROVED_052217_ALL_STRIKEOUTS_REMOVED.pdf.

[157] “Community Police Commission,” City of Seattle, accessed July 12, 2022, https://www.seattle.gov/community-police-commission/about-us#commissioners.