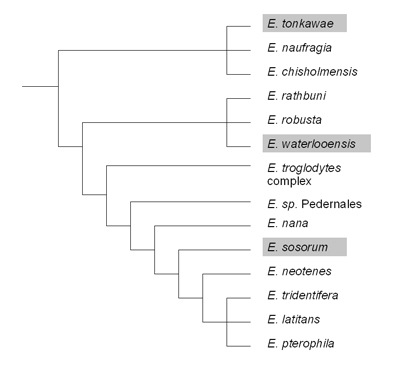

All three Eurycea salamanders that inhabit Austin springs are members of the family Plethodontidae, which is the largest family of salamanders. They are within the sub-family Spelerpinae, which includes four genera: Eurycea, Gyrinophilus, Pseudotriton, and Stereochilus. A total of thirteen species are now described from this group of (mostly) perennibranchiate salamanders that inhabit central Texas.

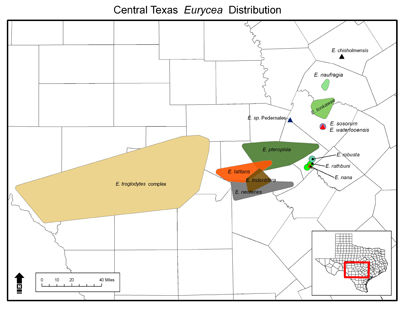

Very little was known about any of Austin’s endemic brook salamanders prior to the 1990s, even though they consisted of three very different species. Prior to discovery and formal description of each species, the majority of brook salamanders (genus Eurycea) found in spring-fed surface streams throughout the Edwards Plateau of central Texas (including the Jollyville Plateau) were considered Eurycea neotenes, the Texas Salamander. In the mid-1990’s, biologists undertook studies to understand the ecology (the relationships between the salamander and its environment) and evolutionary history (e.g., the genetic relationships between the salamander and other species) of this group of salamanders. Through those studies, biologists discovered that the Texas Salamander was, in fact, comprised of several genetically distinct species. The true range of the Texas Salamander is actually restricted to the springs and caves of Bexar, Comal, and Kendall Counties. Two of the newly discovered species were Austin’s own E. tonkawae, the Jollyville Plateau Salamander2, and E. sosorum, the Barton Springs Salamander1.

The primary reason so many different species across a relatively broad geographic range were considered conspecific (the same species) is that all of the Edwards Plateau species are very similar in appearance. Before the invention of methods to examine DNA and protein molecules, differences in physical appearance, or “morphology,” were the basis for distinguishing one species from another. At that time there was no evidence to classify the Edwards brook salamanders as separate species. Once scientists learned how to test molecules and use the results to identify and group species based on their genetic relationships (the science of molecular systematics), the unique genetic characteristics of each species of salamander became apparent, and each could be classified.

Of course there were some exceptions to this prior “lumping” of different species under one name. Most notably are the subterranean species, Austin Blind Salamander, Blanco Blind Salamander, and the Texas Blind Salamander, who exhibit very obvious and extreme differences in the morphology of their bodies and heads. For one, they are “blind,” or to be more specific, they lack an image forming eye. They also tend to have larger, shovel-shaped heads. These features are believed to confer an advantage for living in complete darkness, although scientists still debate the origin of troglomorphic characters as “regressive evolution” or resulting from natural selection. Before the discovery of the Austin Blind Salamander in Barton Springs, the members of this group were considered to be in a different genus altogether (Typhlomolge) because of their extreme morphology. But once again the molecular data2,3 allowed biologists to learn that these species are genetically similar enough to the other Edwards Plateau species to be included in the genus Eurycea.

A cladogram showing the evolutionary relationships of the central Texas Eurycea salamanders. Species that occur in Austin are highlighted in grey. Branch lengths do not reflect genetic distance or substitution rate. Note that none of the species in Austin are each other’s closest relatives; thus illustrating the complex and interesting evolutionary history of this group. From Chippindale et al. 2000 and Hillis et al. 2001.

Range map of all the central Texas Eurycea salamanders.