Fertilization of Trees

Written by Keith Babberney | Forester | Community Tree Preservation Division | City of Austin

In Austin, we love our trees, but we don’t always know the best way to show them our love. People often assume they should fertilize to improve tree health, but plants that are well adapted to Central Texas soils generally don’t need extra nutrients. This article will help you decide if you need to fertilize and what the best methods are to do it.

What is fertilization?

Fertilization simply means adding material to soil (or sometimes directly to plants) that provides the elements plants need. Trees, like all plants, require certain specific nutrients to survive. Most of these nutrients are drawn from the soil by roots and their associated fungal network. If one or more nutrients is lacking, the tree may be unable to complete the process of photosynthesis, which is how plants make their energy.

Though hydroponic gardening proves plants can survive strictly on chemical nutrients, healthy soil is a thriving community of bacteria, fungi, insects, worms, and other living things. Plant stress may be caused by problems in the ecosystem that can’t be helped with fertilizer. For example, in compacted soil, roots struggle to get air and water, so nutrient levels are a secondary concern. In alkaline soils like we have in Austin, certain nutrients may be present but unavailable to plants. Fertilizer should never be added to soil without confirmation that some nutrient is needed. It is important to follow label instructions carefully when applying any product.

Plant health requires more than just nutrients from fertilizer. A healthy soil ecosystem supports healthy trees.

Should you fertilize?

When nutrient deficiencies exist, fertilization can restore the tree’s ability to meet its needs and maintain health and vigor. On the other hand, when required nutrients are already present in soil, adding additional material can cause more problems than it solves.

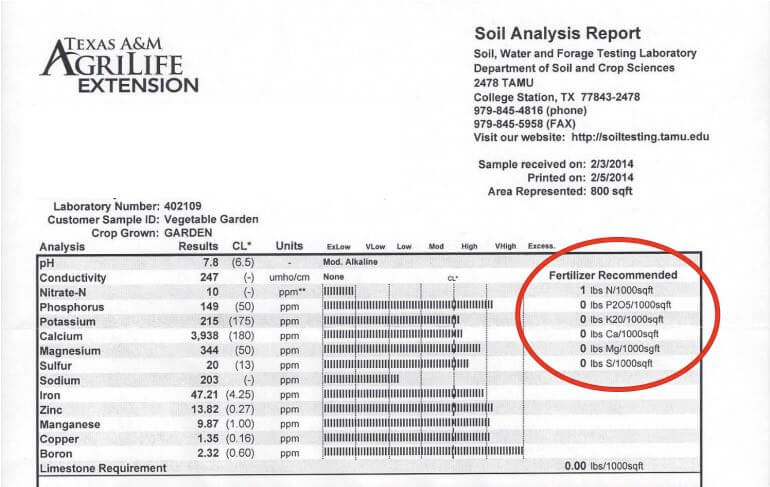

The first step should be to have the soil tested for current nutrient levels. Nurseries sell home kits that can be helpful, but the most reliable option is to send samples to a laboratory for testing. Texas A&M University offers affordable testing that includes full recommendations based on current soil conditions and the plants of concern. Some commercial labs also perform testing services for the public. Basic testing generally measures levels of the three major nutrients (nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus) and most micronutrients (such as iron, calcium, and boron), as well as providing pH analysis. Specialized tests are also available if a particular problem is suspected.

Sending a soil sample to be tested is important to determine what nutrients are needed, if any.

What kind of Fertilizer?

Not all fertilizers are the same. They can be powders, liquids, or granules. The ratio of nutrients and inert ingredients varies from product to product. Packaging should always include three numbers that tell how much of each major nutrient is present. If the bag says “N-P-K 20-10-15,” we know the fertilizer is 20 percent nitrogen, 10 percent phosphorus, and 15 percent potassium.

If your soil test shows only one nutrient is deficient, you would not want a 20-20-20 product. For example, if you only want to supplement nitrogen, you would look for a package marked with a high first number and low second and third numbers, something like 5-0-0 or 6-1-1. The recommendations from the soil lab would tell you how much of each nutrient to apply per square foot, and a quick calculation would determine how much of the package to use.

Determine the amount of each major nutrient in a bag of fertilizer using the three numbers on the package representing percentage of N-P-K. This 50 lb. bag is 16% nitrogen, so it contains 8 pounds of nitrogen.

Where should you fertilize?

Once you decide which fertilizer to use, you need to know where to put it. Tree roots spread outward from the trunk, extending well beyond the ends of the branches. The deepest roots anchor the tree, while the fine roots that absorb water, air, and nutrients are normally close to the surface. The more soil volume we affect in the root zone, the easier it will be for the tree to take advantage of the improvements.

It may be necessary to treat your whole yard to reach all your tree's roots.

On urban and suburban lots with mature trees, this usually means we want to treat the entire yard. Turf grass often becomes significant to the job. Grass forms a dense mat of roots that compete well for soil resources, particularly water. While grass roots normally only grow down a few inches, trees can have feeder roots up to two feet deep.

Of course, not all soils are even one foot deep, and some soils are so compacted that roots can’t grow very deep. The basic principle is that the roots we want to reach are close to the surface, spreading as far as 3 times the height of the tree. Any product we add to the soil will be more available to the tree when and where water is present. With this in mind, there are four basic ways to provide what’s needed to the trees. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

How should you fertilize? Four Options

-

Surface Application

The simplest method—and often the cheapest—is to broadcast materials over the surface of soil and let gravity and water carry it to roots. Plants have evolved to get their nutrients this way, and it still works fine. A wide range of products can be broadcast; they are sold as powders, granules, or pellets. They can be spread by hand with scoops or shovels, or a wide range of machines are available that can help distribute materials evenly over a large area.

Timing of surface applications can be important. Adding a concentrated chemical to plants during hot, dry weather can cause “burning” damage to plants, so it’s better to apply granular fertilizers during mild weather. Often, spring and/or fall are preferred. No matter when it is applied, fertilizer should be watered in after spreading to wash the chemicals from the plants and carry them into the soil. Trees prefer a slow, deep soaking to a short, light sprinkle.

This is not as big an issue when organic materials of lower concentration are used (such as N-P-K 1-0-0 instead of 20-0-0). A quality compost can be spread up to ½” thick any time with little risk of damage to plants. Not only does compost provide mild levels of nitrogen, but as it decays it feeds and invigorates the soil ecosystem. Healthy soil supports healthy plants.

However, surface application is not always the best choice. Some disadvantages include:

- On steeply sloping lots or severely compacted soils, fertilizers may wash away before they can be absorbed into the soil, which not only wastes money but can cause problems for wildlife along our creeks and lakes.

- It often requires a lot of work to move heavy bags around and spread the material.

- A big pile of compost might take up valuable space that has to be reclaimed quickly.

- Damage to plants can occur if products are not spread evenly. Concentrated pockets of chemical that can be toxic to roots and leaves.

- After spreading, fertilizer should be watered in, which adds a step to the process and might take too much time.

- There may be a delay between application of the product and visible results—which suits trees fine, but doesn’t always sit well with homeowners.

A wide range of devices are available to help spread fertilizer evenly over the surface of a lawn or garden.

2. Subsurface Application

Another method of fertilizing is to apply materials directly into the soil, below the surface. This could mean digging a grid of small holes and filling them with dry fertilizer. Some companies offer fertilizer “spikes” that can be pushed into the soil, where they slowly dissolve and become available to plants. The problem with these techniques is that the material does not readily move through the soil. It leads to isolated pockets of toxic soil, surrounded by larger pockets of soil where plants can access the nutrients. The majority of the soil remains unaffected.

The most effective subsurface technique is often marketed as “Deep-root” fertilization or feeding. Fertilizer is dissolved in a large tank of water. A large, metal spike is pushed into the soil and the liquid is pumped by a machine below the surface. This requires specialized equipment, so generally professional arborists or landscape companies are the ones to do it. Some consumer equipment can work in a similar way, but tends to be much smaller and slower to treat a large area.

There are several advantages of deep-root applications:

- The liquid is injected below grass roots, so trees can benefit without having to settle for what the grass leaves behind.

- Because it goes directly into soil, there should be little or no runoff with this method.

- The solution used can be customized to include soil conditioners, like humates or mycorrhizae.

- Nutrients are potentially available to the plant immediately.

- Chemicals and are not as likely to burn plant tissues because they are diluted and spread out through the soil more effectively.

- The injection needle can puncture layers of compacted soil, allowing water, air, and nutrients to penetrate more deeply than they would with surface application.

This method can be problematic, though.

- In severely compacted, shallow, or rocky soil, it may be impractical to insert the injection wand deep enough to penetrate the grass.

- In softer soils, the needle may go too deep and place the chemicals below the tree roots, where it is wasted.

- The liquid sometimes splashes out of the injection sites, which can be messy, and some chemicals may stain concrete or other hardscape.

- Pressure from the pump sometimes pushes up large plates of soil, which can shear off delicate feeder roots between the plates.

- And, because the equipment is somewhat large and expensive, it can create logistical headaches and might not be affordable to smaller companies or individuals.

Arborist Salvdore Martinez uses a deep-root injection system to pump liquid nutrients and soil conditioners below the soil surface. Photo courtesy Arborilogical Services.

3. Direct Injection

Another possibility is to inject liquid nutrients directly into plant tissues.Small holes are drilled through the bark of the tree trunk or primary roots into sapwood, then specialized equipment is used to push the chemical into the tree’s vascular system.Several techniques and devices are available for these injections.

As an ongoing maintenance plan, injections are not a good choice.

- The drilled holes can provide entry for decay or disease organisms.

- Injected chemicals don’t always move through the tree as well as what comes in through roots naturally.

- The chemical is often quite concentrated, which can damage the tree’s cells at injection sites.

- Even at their best, injections only have a short-term effect on the plant and no effect on the soil.

- Without some kind of soil remediation, the process would have to be repeated at some interval, perhaps annually, requiring new drilling each time.

Still, injections have their place. The effect is almost immediate, so if there’s a question about which nutrient is deficient, injections can be used to diagnose the problem. If the soil is severely compacted, steeply sloped, or very limited in volume, injections or spraying may be the only practical ways to get adequate amounts of the chemicals into the plant.

On difficult sites, fertilizer can be directly injected into tree trunks opr surace roots.

4. Foliar Application

A final technique involves dissolving nutrients in water and spraying the solution onto the leaves of plants. The nutrients are absorbed through the leaves to become available for photosynthesis and other processes. Like injections, spraying is not usually a good choice for ongoing treatments.

- Timing is critical to ensure the leaf pores are open and active to absorb the chemicals.

- The effect is short-lived and does little to improve the soil in the root zone.

- As with any spraying, wind might blow the chemicals onto other plants or property where it isn’t needed and might cause staining or other problems.

- Technicians may struggle to get adequate coverage on the highest leaf surfaces to have a significant effect.

Like injections, foliar treatments can be useful in certain situations. The effects of spraying will be evident quite rapidly, so it can help diagnose a deficiency when other methods are inconclusive, and on difficult sites injection or spraying may be the only two practical methods to affect a particular tree.

A qualified arborist can help you determine if your trees need treatment and if so, which methods are best suited to your landscape. To find one, and to learn more about proper tree care practices, visit our Tree Information Center.

Article written by Keith Babberney, Forester with the City of Austin's Community Tree Preservation Division.

This information is sponsored by the City of Austin. Learn more about trees and resources at the Tree Information Center!