Lady Bird Lake: Fiction or Fact?

Town Lake... Lady Bird Lake... the Colorado River. Whatever you call it, Austin wouldn't be the same without the scenic body of water separating North and South Austin.

Many residents and visitors appreciate Lady Bird Lake's beauty, whether from a kayak, the hike-and-bike trail, or even while stuck in MoPac traffic. But even many longtime fans have heard inaccurate information about our fair Lady along the way. We're here to test your knowledge and help set the record straight.

Fiction or Fact? Lady Bird Lake is a lake.

FICTION. Let's start with the name itself. Putting aside the kerfuffle over whether to call it by the current official name, Lady Bird Lake, or the old name, Town Lake, the truth is it's a reservoir. A "true" lake is created by natural processes, while a reservoir is formed by a dam. Lady Bird Lake is a dammed section of the Colorado River.

In Austin’s early years, the Colorado River flowed unimpeded through the town. Over time, dams were constructed for various purposes, and many were destroyed during flood events. The Longhorn Dam was built in 1960 to provide a cooling pond for the Holly Power Plant. The original purpose is now obsolete (the Holly Power Plant was decommissioned in 2017), but no plans exist to remove the Longhorn Dam.

Fiction or Fact? Lady Bird Lake's water level changes due to floods and drought.

MOSTLY FICTION. Lady Bird Lake gets its water from Lake Austin, Barton Springs, and feeder creeks (or “tributaries”), including Shoal Creek, East and West Bouldin Creeks, and Waller Creek. Normal inflows from these sources can raise the water level in Lady Bird Lake for a short period of time; however, once the reservoir’s water reaches a certain height, it flows out through two bascule gates in Longhorn Dam. Bascule gates allow water to passively flow over the top of a dam anytime the water reaches that height, as opposed to “lift gates” that are controlled to open during more extreme weather events. Lady Bird Lake is known as a “pass-through” or “flow-through” system, because water passes through the reservoir and continues its journey down the Colorado River to Matagorda Bay, usually without requiring the opening of the dam’s flood gates. Longhorn Dam differs from dams designed primarily for flood control, such as the Mansfield Dam at Lake Travis, which hold back great volumes of flood water.

During times of flooding, the Longhorn Dam has seven flood control gates that can be opened. During times of drought, Lady Bird Lake typically stays full, thanks to a combination of inflows from Barton Springs and water released from Lake Travis that also keep Lake Austin full. So, the water level in Lake Travis rises and falls with floods and droughts, but Lady Bird Lake’s water level stays constant.

Fiction or Fact? Swimming is not allowed in Lady Bird Lake because the water is polluted.

FICTION. With three of Austin’s most popular off-leash areas (Red Bud Isle, Norwood Park, and Auditorium Shores) located on Lady Bird Lake, you might wonder why your dog can swim here, but you can’t.

Since Lady Bird Lake is located in the heart of our large city and is partially fed by creeks that wind through urban landscapes, it’s easy to assume that the water quality is too polluted to be safe for swimmers. However, swimming was banned on Lady Bird Lake as long ago as 1964 due to several tragic drownings caused by hazards under the water’s surface. Remnants of old, washed-away dams, deep pits from old gravel mining operations, and other types of debris litter the bottom of the reservoir, creating a dangerous underwater landscape.

Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring, published in 1962 made famous an Austin chemical plant's devastating insecticide spill that wreaked havoc on the environment for approximately 140 miles. However, pollution in the reservoir was not a noted concern for swimmers back then (see the public discussion minutes on page 16 from the May 28, 1964 City Council meeting that resulted in the eventual swim ban). According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), levels of DDT (one of the insecticides of concern) peaked in 1960s, but are no longer a concern in the reservoir sediment. Our scientists routinely monitor the water quality of Lady Bird Lake and annually provide the results online as part of the Austin Lakes Index. In 2017, Lady Bird Lake's water quality was rated "Fair" and is considered safe for contact recreation. Since the unsafe debris remains submerged in the reservoir, swimming is likely to remain off-limits for the foreseeable future, except for permitted events.

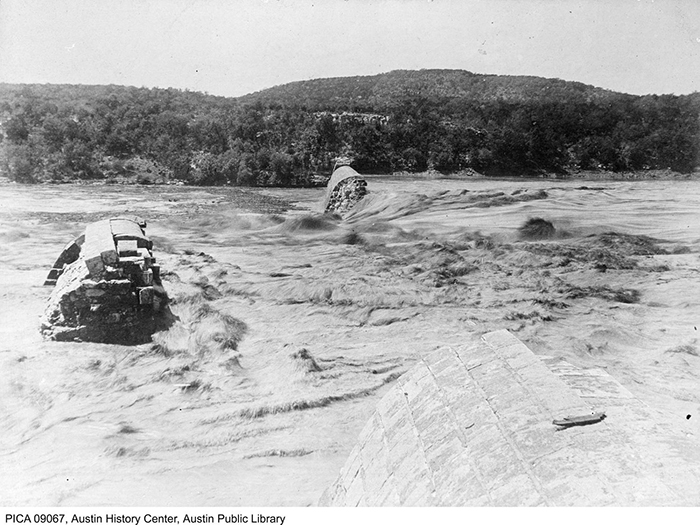

This image from 1900 shows floodwater breaking apart the original Austin Dam between Lake Austin and Lady Bird Lake (where the Tom Miller Dam now stands). Several floods have washed debris into the reservoir.

Fiction or Fact? Every water snake you see in Lady Bird Lake is a water moccasin (aka cottonmouth).

FICTION. The majority of the large, dark-colored snakes you might spy swimming in the water or sunbathing on the banks are UNLIKELY to be water moccasins.

All snakes can swim, many snakes in Austin are large and dark-bodied, and a few types of snakes spend most of their time in or near water. Chances are very high that a water snake you see on Lady Bird Lake is a nonvenomous snake of the genus Nerodia, such as a diamond-backed water snake (Nerodia rhombifer rhombifer) or a blotched water snake (Nerodia erythrogaster transvera). These Nerodia water snakes aren’t shy and may hold their ground if provoked, but they are not aggressive or considered dangerous to people. They primarily eat fish and prefer to avoid humans. If you are lucky enough to spot one of these snakes and have the opportunity to examine its head from a respectful distance, take a look for dark vertical lines on the lips. In the Austin area, those lines are found on nonvenomous water snakes and not on water moccasins, which helps distinguish between the two. Other identifying characteristics, such as pupil shape and head shape, can be difficult to use because the pupils may be hard to see from a distance and because Nerodia can widen their jaws so that their heads temporarily take on the same triangular-shape as a water moccasin.

The nonvenomous Diamond-backed water snake (Nerodia rhombifer rhombifer) has dark, vertical lines on its lips and lives near Austin’s creeks and lakes. (Photocredit) http://mobugs.blogspot.com/2011/10/diamondback-water-snake.html

Water moccasins (Agkistrodon piscivorus), aka cottonmouths, lack dark lines on the lips and are a very uncommon sight on Lady Bird Lake.

Fiction or Fact? Lady Bird Lake is infested with the invasive hydrilla plant.

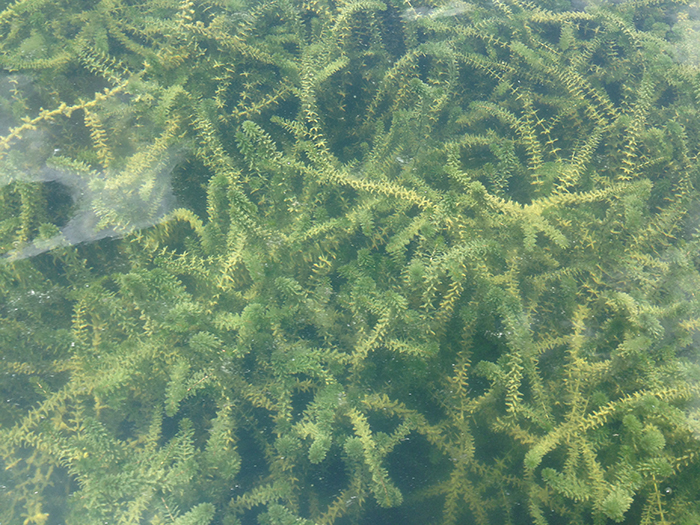

FICTION. If you spend much time in Texas waters, you might have heard about the nuisance plant hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata), a non-native, invasive plant that can cause myriad problems in water bodies. In years past, Lake Austin has been choked with acres of hydrilla, and some parts of Lake Walter E. Long continue to be affected by large mats of it. Curiously, Lady Bird Lake has never been infested, despite its location directly downstream of Lake Austin.

However, fanwort or cabomba (Cabomba caroliniana), a native aquatic plant, occasionally spreads across Lady Bird Lake. While the dense growth of cabomba may alarm rowers and kayakers during the weeks of late summer, the plant is actually very beneficial. Cabomba helps clean the water in Lady Bird Lake by filtering out nutrients, and it provides important habitat for small fish, turtles, and aquatic invertebrates. It is a warm-weather plant and will die back during winter months. Unfortunately, heavy rain events have kept cabomba from flourishing in recent years, but we hope it will establish itself again in Lady Bird Lake.

Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) growing in Lake Walter E Long in 2017

Fanwort (Cabomba caroliniana) growing in Lady Bird Lake in 2015

Fiction or Fact? All of the plants on Lady Bird Lake’s shoreline fell into place naturally.

FICTION. The lake and its surrounding land is highly managed, and people planted many of the trees and plants that grow on the banks and line the trails.

Before the river was dammed, the area in front of Buford Tower (on the north side of Lady Bird Lake, between South 1st Street and Congress Avenue) lacked thick shoreline vegetation. This photo is undated but is likely from the 1950s.

This area is now a "Grow Zone" (an unmowed area along the shoreline) and supports a variety of native plants, including native and adapted varieties planted by people.

We can thank Lady Bird Johnson, Ann and Roy Butler, Roberta Crenshaw, and others who formed the Town Lake Beautification Committee in the 1970s for spearheading the effort to clean up the shoreline and plant trees along Lady Bird Lake, creating the beautiful scene we enjoy today. Now, City staff and resources are dedicated to maintaining Lady Bird Lake, including our Field Operations crew, who remove trash from the water five days a week, and Parks and Recreation Department staff, who provide important daily maintenance work. Additionally, many non-profit organizations also spend time and energy maintaining the lake and its shores. The Trail Conservancy, Keep Austin Beautiful, Austin Parks Foundation, and Tree Folks are a few of the groups that organize volunteers to help keep Lady Bird Lake (and many other parts of town) a great place to spend time outdoors.

Our Grow Zone program protects riparian (waterside) areas from mowing to allow beneficial plants to grow between the water and nearby urban areas. A healthy buffer of vegetation helps to keep some pollutants and trash from reaching the water, prevent shoreline erosion, and provide important habitat for urban wildlife. Our staff routinely remove patches of invasive plants, such as giant cane (Arundo donax) and elephant ear (Colocasia esculenta) from the shoreline to help a diverse mix of native plants to grow.

Our crews removed a large patch of elephant ear from this stretch of the shoreline (just downstream of the First Street Bridge on the north side of the lake) and planted a mix of native, water-loving plants. The area is now a diverse, productive wetland.

Fiction or Fact? You can't eat fish from Lady Bird Lake.

FICTION. (With caution.) In 1987, the Austin-Travis County Health Department issued a health advisory (based on fish tissue samples from 1985), stating that people should not consume certain fish species from the lake, due to elevated concentrations of Chlordane. This advisory was extended to all fish in 1990.

Chlordane was once a commonly used pesticide for termite treatment, but the EPA banned it in 1983. Chlordane levels in fish have dropped over time, and state officials withdrew the fish consumption advisory in 1999. Although no current advisory prohibits the consumption of fish caught in Lady Bird Lake, it's an important safety precaution to research fishing advisories prior to eating fish from any body of water.

Today, Lady Bird Lake is a popular fishing lake and is rated “excellent” for largemouth bass angling and “good” for sunfish. In fact, Lady Bird Lake has produced more state record fish (based on a combination of length and weight records) than anywhere else in Texas.

Fiction or Fact? A green-eyed monster lives in Lady Bird Lake.

FACT-ish. As you can see from this photo, the monster's eyes are black and white, not green.

Seriously, though…This structure, now painted with eyeballs and helping to keep Austin weird, is a remnant of a larger structure used by the old Green Water Treatment Plant and the original power plant.

This aerial photo from 1940 shows a structure at the same location as the green-eyed monster. The Green Water Treatment Plant and the original power plant (that would become the Seaholm Power Plant) were located north of the river on either side of Shoal Creek.

Fiction or Fact? You are a Lady Bird Lake expert.

FACT. You're now qualified to set the record straight on the most persistent myths related to Austin's favorite lake-not-a-lake. Dazzle your friends with your newfound knowledge and be sure to experience Lady Bird Lake in person!