Celebrating 30 Years of the Comprehensive Watersheds Ordinance

Before the Watershed Ordinance

In the 1970s and 1980s, development raced across the Texas landscape, sprawling into the land in and surrounding Austin. As urban development pushed into the canyons, hillsides and prairies, our creeks, lakes and aquifers were impacted by increases in concrete and other impervious cover from construction. Small tributaries containing springs and wetlands were filled to build streets and buildings. Caves and sinkholes were filled with dirt, concrete, or used to dispose of polluted roadway runoff. The Edwards Aquifer was at risk from these actions. These construction activities caused the erosion of the thin soils covering the Texas Hill Country. As rainwater flowed over the land towards area creeks, sediment clogged caves and sinkholes. Members of the community who fought to protect our drinking water and who cherished the unique beauty of our hometown persuaded the City Council of Austin to act to prevent further degradation of our water and natural resources.

Stormwater runoff from a construction site. The cloudy appearance of the water is from sediment.

This cave was filled in the 1980s. Later, it was excavated to map the passages and establish a buffer prior to development.

Protecting our Water Supply

In 1980, the Lake Austin ordinance was the first of several watershed-specific ordinances to enact protective measures such as restricting construction on steep slopes, limiting “cut and fill” (no excavating or filling in an area), requiring erosion control and land restoration. More ordinances with similar water quality requirements followed: the Williamson Creek Watershed Ordinance, the Barton Creek Watershed Ordinance and the aquifer-related Slaughter, Bear, Little Bear and Onion Creek watersheds Ordinance. As development continued, the need for protection in all watersheds was recognized.

The City Council and staff researched and identified land use regulations that would protect our water supply and preserve the characteristics of the natural environment, resulting in the Comprehensive Watersheds Ordinance (Ordinance No. 860508-V) that went into effect on May 19, 1986.

The principles set forth a number of progressive environmental protection measures by

- placing limitations on the density of development and on the amount of impervious cover in all watersheds outside of the urban core,

- limiting development on steep slopes and along creeks,

- requiring the use of erosion and sedimentation controls for construction sites,

- defining and requiring the protection of Critical Environmental Features,

- establishing creek buffers (called Critical Water Quality Zones-CWQZ),

- requiring structural water quality controls and

- limiting the disruption of natural terrain (cut/fill restrictions).

How do the requirements of the ordinance reduce non-point source pollution and preserve Austin’s natural beauty?

By protecting environmentally sensitive terrain with the intention of leaving the creeks, lakes, cliffs, canyons, caves, sinkholes, springs and wetlands intact, and by removing pollutants from developed areas before they are allowed to flow into our creeks. Not only does this protect water quality but it helps preserve the natural environment and provides a secondary benefit of recreational enjoyment.

What are the types of Critical Environmental Features?

Cave. A natural underground cavity, chamber or series of chambers formed by the dissolution of limestone by surface or groundwater.

Cave entrance in the Northern Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone. Water enters directly through the hole and via fractures in the rock near the entrance.

Sinkhole. A closed depression formed by the dissolution of limestone and a point of recharge (replenishment of the aquifer by water).

Old Farm Sink is a sinkhole located south of the Will Hampton Library on Convict Hill Road. This sinkhole drains slowly enough that it supports a wetland but water does recharge to the Edwards Aquifer.

Spring. A point or zone of natural groundwater discharge having a measurable flow and/or a pool.

Cold Spring gushes from the southern bank of Ladybird Lake. Water from Barton Creek flows into a sinkhole, travels within the Edwards Aquifer and discharges to this spring. Click here for a map of springs that you can hike or paddle to.

Wetlands. Lands transitional between terrestrial and aquatic systems where the water table is at or near the land surface.

The wetland fringe along this creek prevents sediment from washing into the creek. A Critical Environmental Feature buffer will capture sediment running off of development and allow stormwater to infiltrate and support baseflow in the creek. Now, that’s some clear water!

Canyon Rimrock. A steep rock face with a horizontal extent of 50 feet or greater length and 4 feet or greater height. Most commonly found paralleling the side of a canyon or surrounding a canyon head.

The tributaries of Bull Creek expose dramatic limestone layers. Buffers help slow runoff, capture sediment, prevent erosion and prevent direct disturbance of the rock. Rimrock sometimes has a seep along a porous rock layer or a shelter cave may form where rock is eroded away.

Bluff. An abrupt vertical change in topography of 40 feet or greater in height.

Bluffs are protected for the same reasons that canyon rimrocks are protected: to prevent erosion. They also are unique, somewhat rare features that contribute to the “natural and traditional character” of Austin.

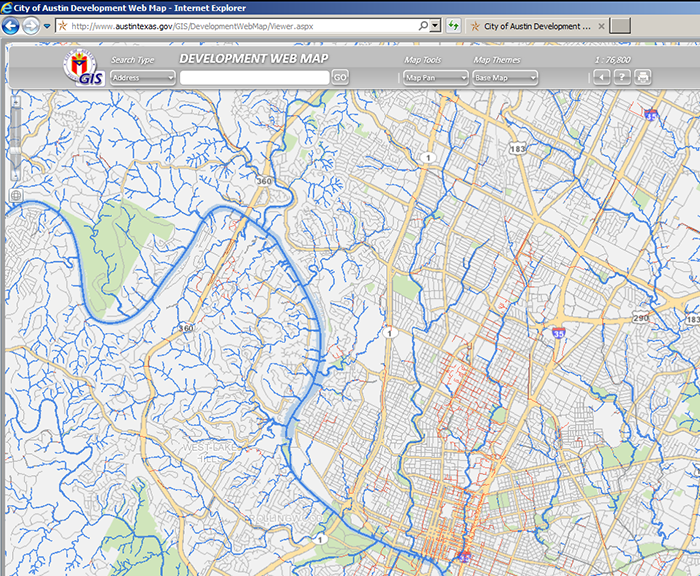

Critical Environmental Features (CEFs) are present all over Austin, occurring in the canyons, creeks, uplands terrain and along our lakes. In the last 30 years, City of Austin staff have identified over 4,780 CEFs; primarily during the site plan and subdivision review process!

Look for CEFs in your area (Microsoft Silverlight is required to view this map)

All of the strategies included in the Comprehensive Watersheds Ordinance have resulted in preserving our watersheds and protecting our drinking water supply. In the 30 years since the ordinance went into effect, additional water quality protection ordinances have been adopted by the Austin City Council. In 1992, citizens voted and approved the Save Our Springs Ordinance, which reduced impervious cover limits and enhanced stormwater treatment in the watersheds contributing to Barton Springs. In 2013, the Watersheds Protection Ordinance modified the requirements for creek buffers to provide greater protection for the headwaters of our creeks and to establish Erosion Hazard Zones along creeks. More information on the CWO and later ordinances are available on the Watershed Protection Department’s website at: www.austintexas.gov/watershed

As you’re out enjoying our creeks, the lakes and Barton Springs, remember the efforts of the citizens and City Council to keep our drinking water supply clean and to provide recreational opportunities by enacting the Comprehensive Watersheds Ordinance!